Mt Feathertop: history, huts and hikes

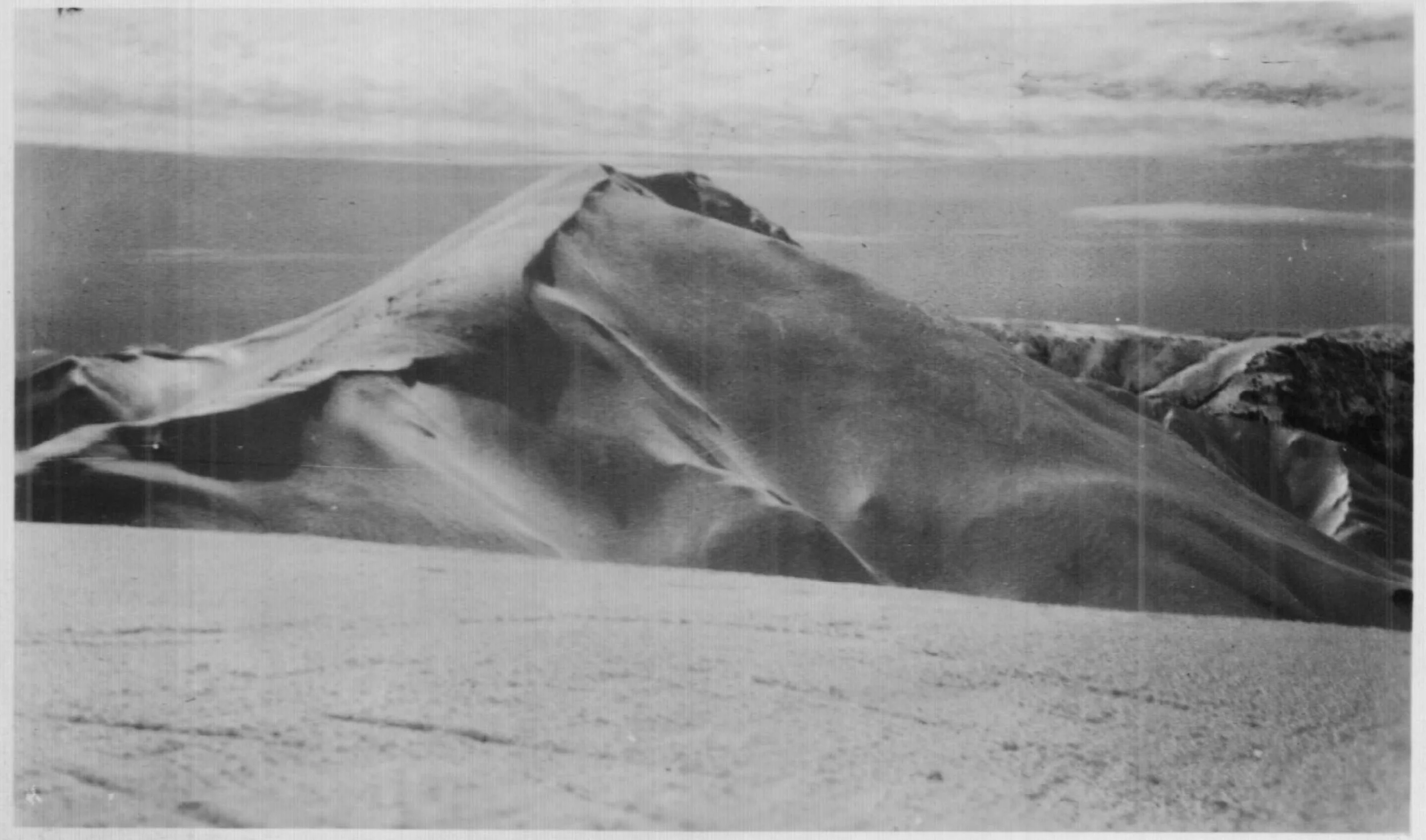

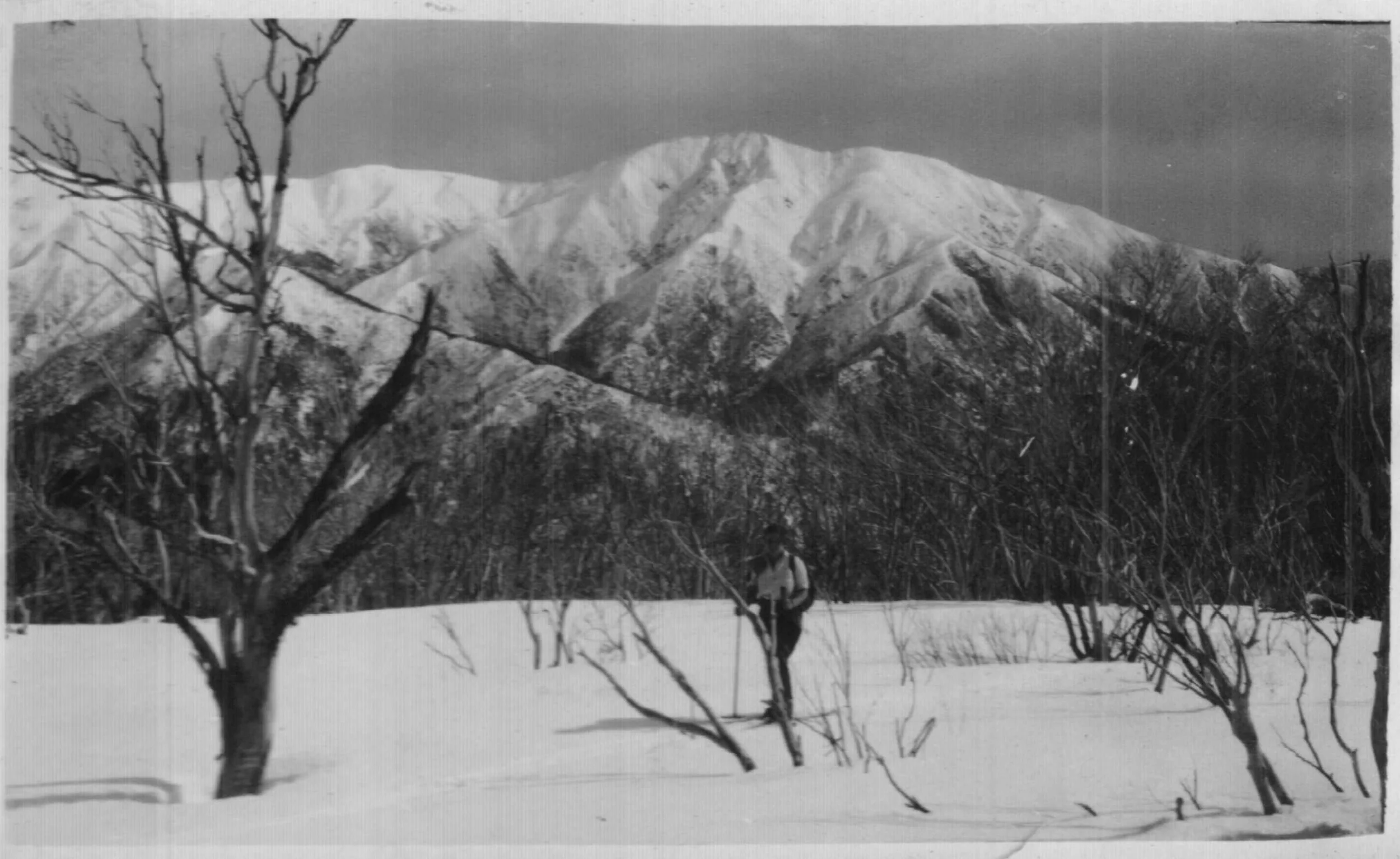

The classic winter view of Mt Feathertop from Mt Hotham ski resort.

© David Sisson

Mt Feathertop is the second highest mountain in Victoria and one of the most picturesque peaks in the state. It is joined to nearby Mt Hotham by The Razorback, a high narrow ridge, but is otherwise surrounded by steep slopes. It has a sharply defined summit ridge rather than the rounded domes of many nearby peaks.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries the mountain hosted gold mines and mountain cattlemen, but as the gold ran out, the activity it provided on Feathertop was replaced by tourism. The Feathertop Bungalow operated as a commercial ski lodge from 1925 to 1939 and the mountain almost became a major ski resort. Today it has reverted to a relatively isolated and undeveloped peak with only two refuge huts.

In addition to the history, brief descriptions of eight walking routes on Mt Feathertop are included, they can be found in section 8 of this article. Finally this is a long article, with around 25,000 words and 60 illustrations when I last checked, so while it's designed to be phone friendly, it is best read on a computer or large format tablet.

The classic view of Mt Feathertop in winter. 1930 Kath Magill.

© David Sisson. 2015 - 2018.

The summit ridge in summer viewed from the Razorback. Photo: © Blair Hamilton.

Contents

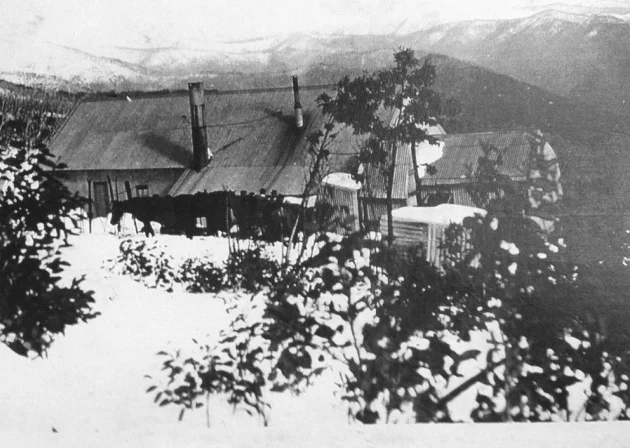

The Feathertop Bungalow in 1935. Photo: Mick Hull.

Click on main chapter headings to go to that section.

1. Mt. Feathertop: naming, mining and grazing

- Gold mining

- Mountain cattlemen3. Early days of the Feathertop Bungalow

- Planning and construction

- Opening and operation

- Difficulties with land tenure4. The last decade of the Bungalow

- Transport

- Skiing

- Destruction5. Post war events and proposals

- Feathertop is overtaken by other ski destinations

- Tracks and management

- Walking track development

- Management

- The Cross

- Three development proposals

Hydro electric plans

A chairlift for Feathertop

Razorback railway station6. Huts

- Feathertop Hut

- Razorback Hut

- MUMC Hut

- Old Federation Hut

- New Federation Hut

- Proposed High Knob huts8. Hiking routes on Mt Feathertop

- Winter access

Appendices. Historic documents on Mt Feathertop

9. Feathertop buildings in 1936. Cleve Cole & Roy Weston

10. Feathertop Bungalow documents

- The Chalet at Feathertop. Gordon Langridge

- The opening of the Feathertop Bungalow

- 1928 arrangements for the Bungalow

- Ada Banks, manager of the Bungalow

- The Bungalow on Feathertop. Bob Croll

11. Articles from the 1920s

- Feathertop Snow Carnival 1923. F. Barker

- Scaling Feathertop & crossing the Razorback 1926. J. Tulloch13. MUMC Hut documents

- Description of hut design. Peter Kneen

- Building the MUMC Memorial Hut. Phil Waring

1. Mt. Feathertop: naming, mining and grazing

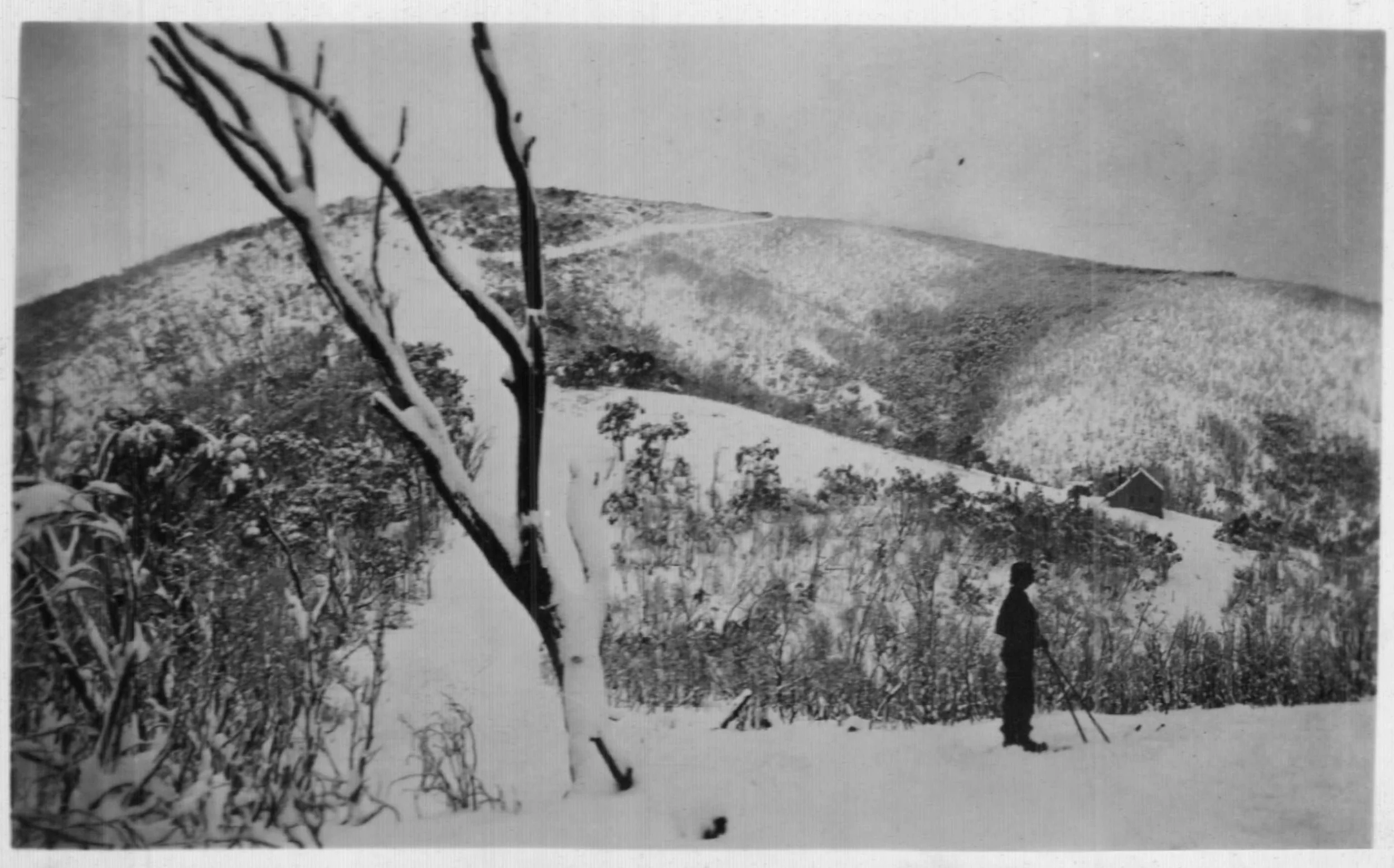

Mt Feathertop from the Bogong High Plains in the 1920s. Photo Robert 'Wilkle' Wilkinson. Source National Library of Australia.

Mt Feathertop was sighted and named in early 1851 by Jim Brown and Jack Wells, stockmen from Cobungra Station. While looking for summer pastures they became the first non aboriginals to systematically explore and name locations around the Bogong High Plains. They named the mountain after the feather shaped plume of cloud that is often seen downwind from the summit. They dubbed nearby Mt Hotham 'Baldy'.

The mountain was first climbed in 1854 by explorer and Government Botanist, Dr Ferdinand Mueller (from 1871, Baron Ferdinand von Mueller), who was unaware that the name Feathertop was already in use by cattlemen and gold prospectors. He suggested that it be named Mt Hotham after Victoria's newly appointed governor.

Mt Feathertop from the Ovens Valley goldfields in 1863. Lithograph from an original by Nicholas Chevalier

Graziers took up runs in the upper Ovens valley in the late 1830s. However the area was fairly sparsely settled before the gold rush. Gold was found near the base of the mountain at Harrietville as early as 1852, but the big rushes were at nearby Wandiligong and the Buckland Valley. The prospectors and miners naturally picked up the names used by local farmers and pastoralists. As farms were established and the area became more closely settled, these names stuck and titles given by von Mueller and later surveyors have, with a few exceptions, vanished. However the name Hotham was transferred to the peak we now know by that name. The original cattlemen's name for the peak 'Baldy' survived in Little Baldy, a nearby hill that was never renamed Little Hotham.

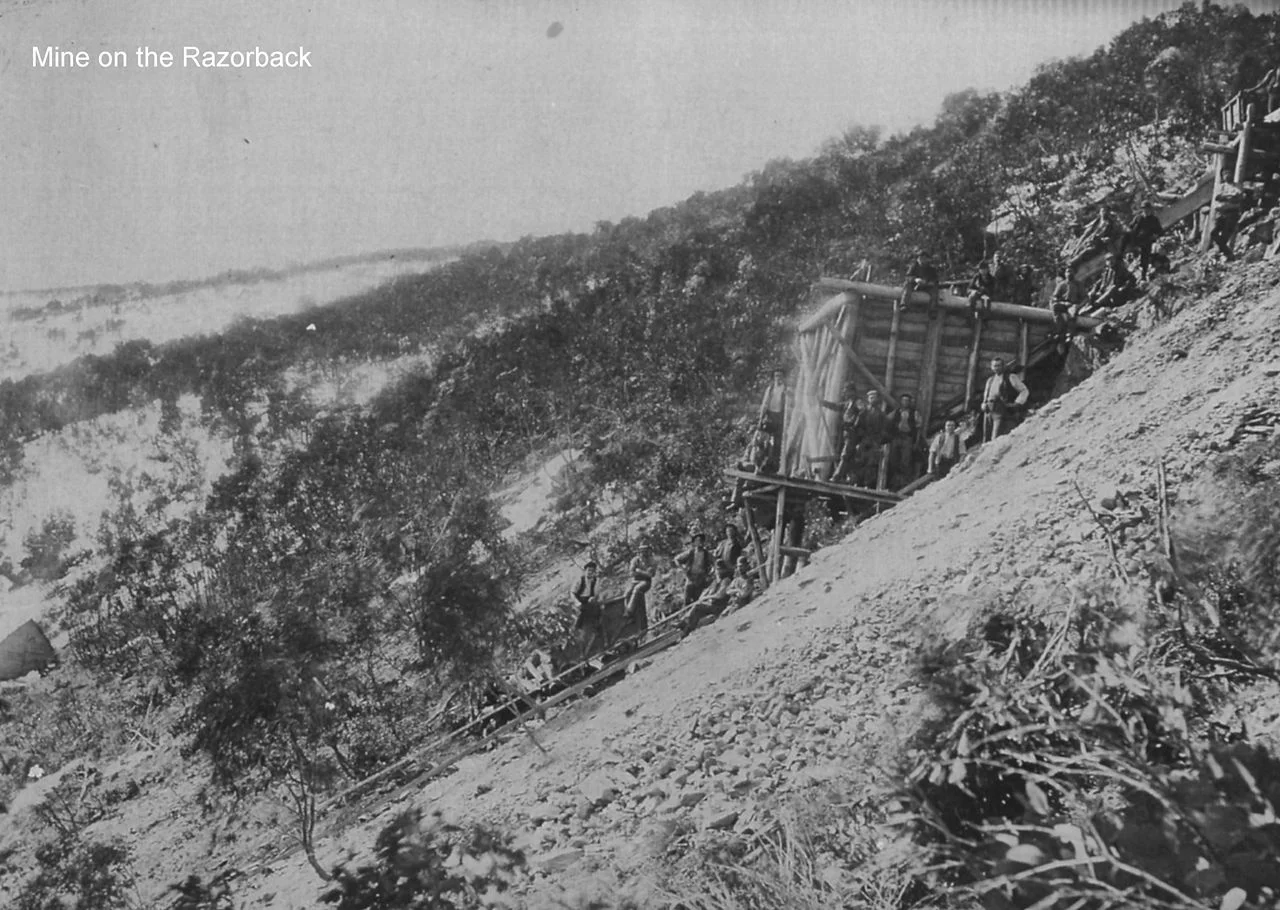

Ore bin at the Razorback mine.

Gold mining

Mining occurred on the slopes of Feathertop from the 1870s to the mid 20th century. The Champion Reefs on the spur of the same name were mined from 1868 to 1874 producing 1,927 troy ounces (60 kg), before the gold ran out. Attempts to revive the mine were made from 1920 - 1925 and in 1945, but no more gold was produced.

The Razorback Mine operated intermittently on the Razorback from 1895 to 1903. It was about 1½ km south of where Champion Spur joins the Razorback; remnants were visible after the 2003 fires. Another mine on the Razorback was operated by The Government Grant and Birthday Gold Mining Co. which in 1895 built a large water powered crushing battery with a 1 km inclined tramway connecting it to the mine. But the ore did not live up to forecasts and it only produced 55 ounces (1.71 kg) before being abandoned in 1897. Tribute parties mined a little more before the mine and battery were burned by wildfires in 1906. (Tribute mining was an arrangement where the owner of an unused mine allowed independent parties to extract ore in return for a percentage of the proceeds.)

Battery used to crush ore at the Razorback Mine. Photo from Alpine Shire history

More information on mining can be found in: Brian Lloyd's. Gold at Harrietville. Shoestring Press, 1982. Also worth a look is Andrew Swift's Beneath the Razorback, a DVD on the history of mining on the Razorback with visits to locations to the sites of mines, batteries and relics. It is available from Heritage Rat Productions.

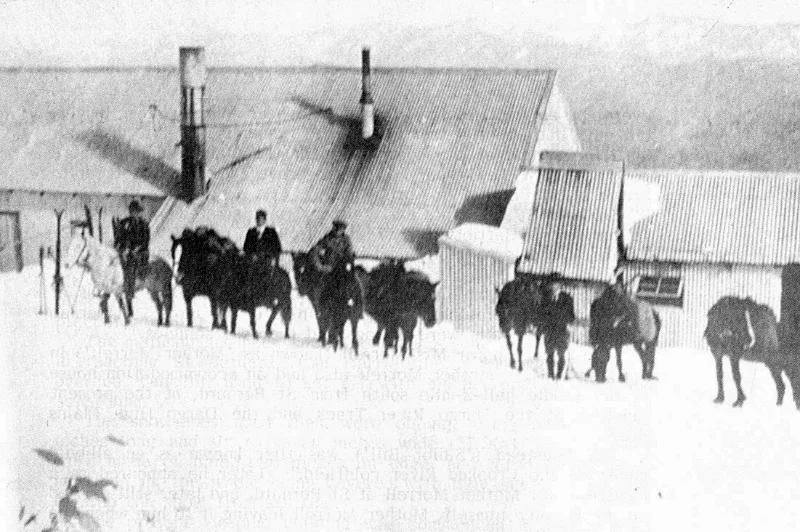

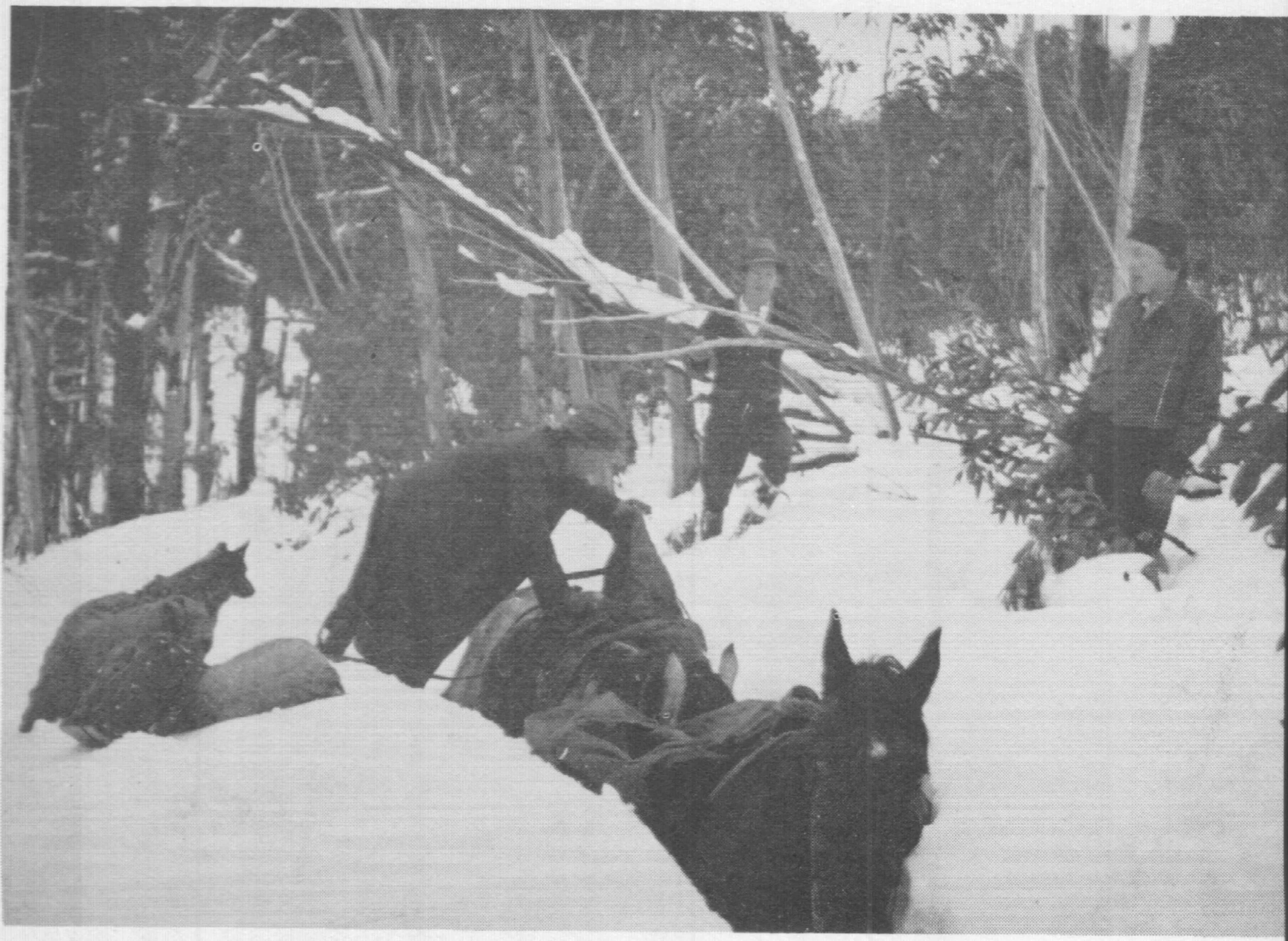

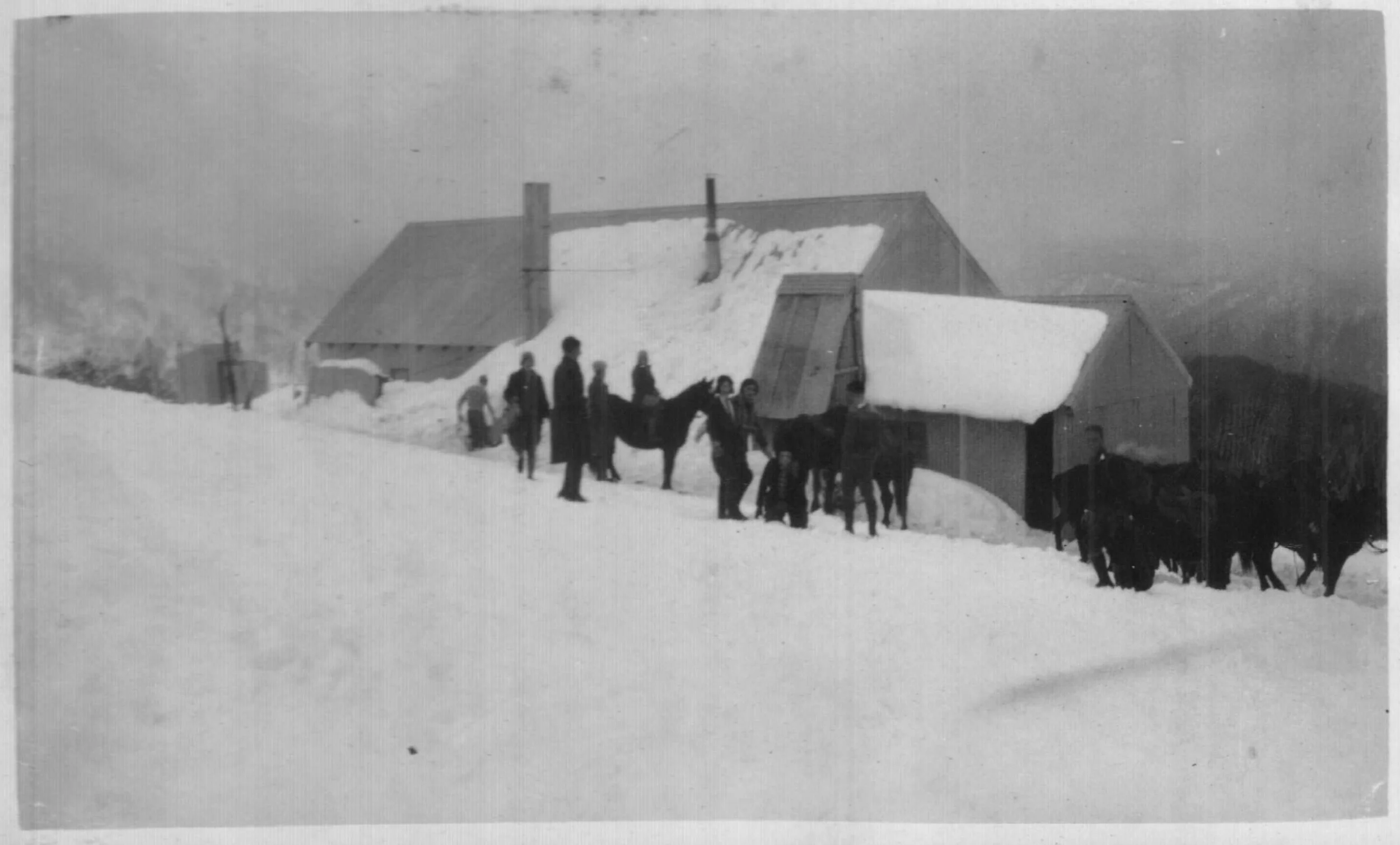

Lawler family cattlemen on Feathertop, probably early 1930s.

Mountain cattlemen

Graziers found things harder on Mt Feathertop than on nearby mountains, the steep slopes made grazing and mustering difficult. Nevertheless after summer grazing runs had been taken up on the gently graded Dargo High Plains, farmers looking for new summer pastures ventured on to Mt Feathertop. Cattlemen active on Feathertop included John Howard and many members of the Lawler family who droved cattle from their property on Snowy Creek at Freeburgh, up Dungey's Track to the North Razorback, over a rough pad to the west of the summit and on to Mt Hotham. Their yards were in Corral Saddle between Mount Hotham and Mt Higginbotham, near the modern Corral car park.

From the mid 1920s, 'run 29' in the area around the top of Bungalow Spur was held by Jack Keating. He had a property near Harrietville which was connected to his run by a good track up Bungalow Spur. With Feathertop Hut providing shelter, in contrast to other Feathertop cattlemen, Keating had a fairly easy muster of his cattle.

Boundary of Feathertop grazing run from an unpublished paper by Peter Cabena for the Lands Department. Mount Hotham: its history from the 1850s to 1950s, 1979.

While Razorback and Feathertop huts were used by mountain cattlemen, it appears that no huts were built by them on Feathertop. The Lawler family conducted their operations from their huts at Stony Tops at the far north end of the Razorback, Snake Valley (the West Kiewa River) and at Mt Hotham. Feathertop's steep slopes meant that grazing was never an easy proposition after concerns about soil erosion were raised, grazing leases were withdrawn in 1958. The affected cattlemen were mostly compensated with leases elsewhere. It appears that limited grazing continued on parts of the Razorback until 1978 although it is fairly certain that cattle were excluded from the mountain itself.

The boundaries of the Feathertop run were fairly fluid and it was sometimes split between two parties, but it usually included the north and south Razorback in addition to the mountain itself. The lease holders were:

1888 - 1893. John Evans of Laceby, near Wangaratta

1897 - 1908. Jack Lawler of Freeburgh

1905 - 1909. Jack Lawler, Freeburgh

1908 - 1931. Charles Howard, Harrietville

1931 - 1939. Victor Lawler, Freeburgh

1939 - 1945. Vic Lawler & Jack Keating, Harrietville

1945 - 1978. Vic Lawler, J. Keating & Bernard Lawler

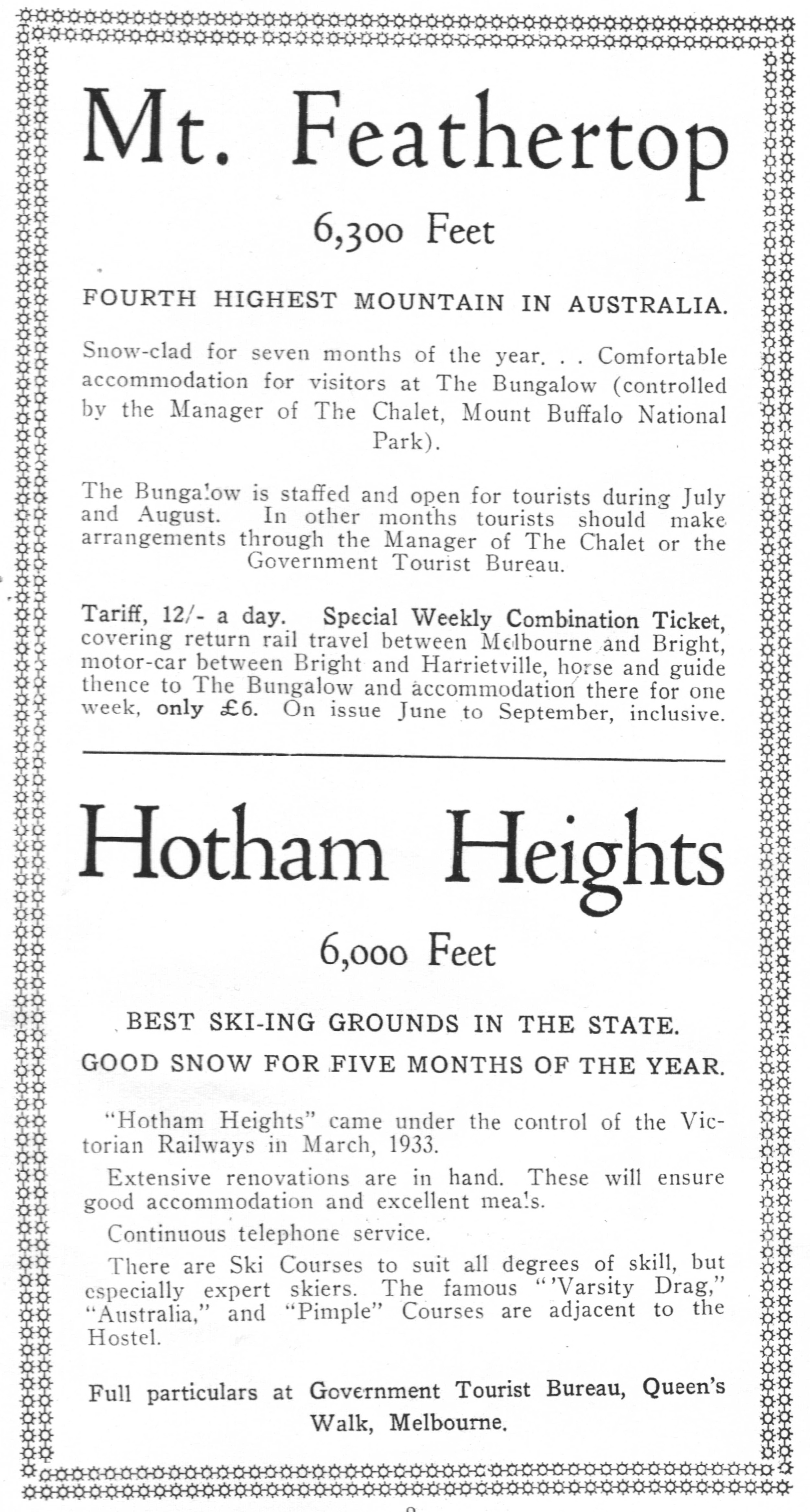

Advertisement in The Herald. Saturday 12 January 1889, p. 1.

2. Early tourism and skiing on Feathertop

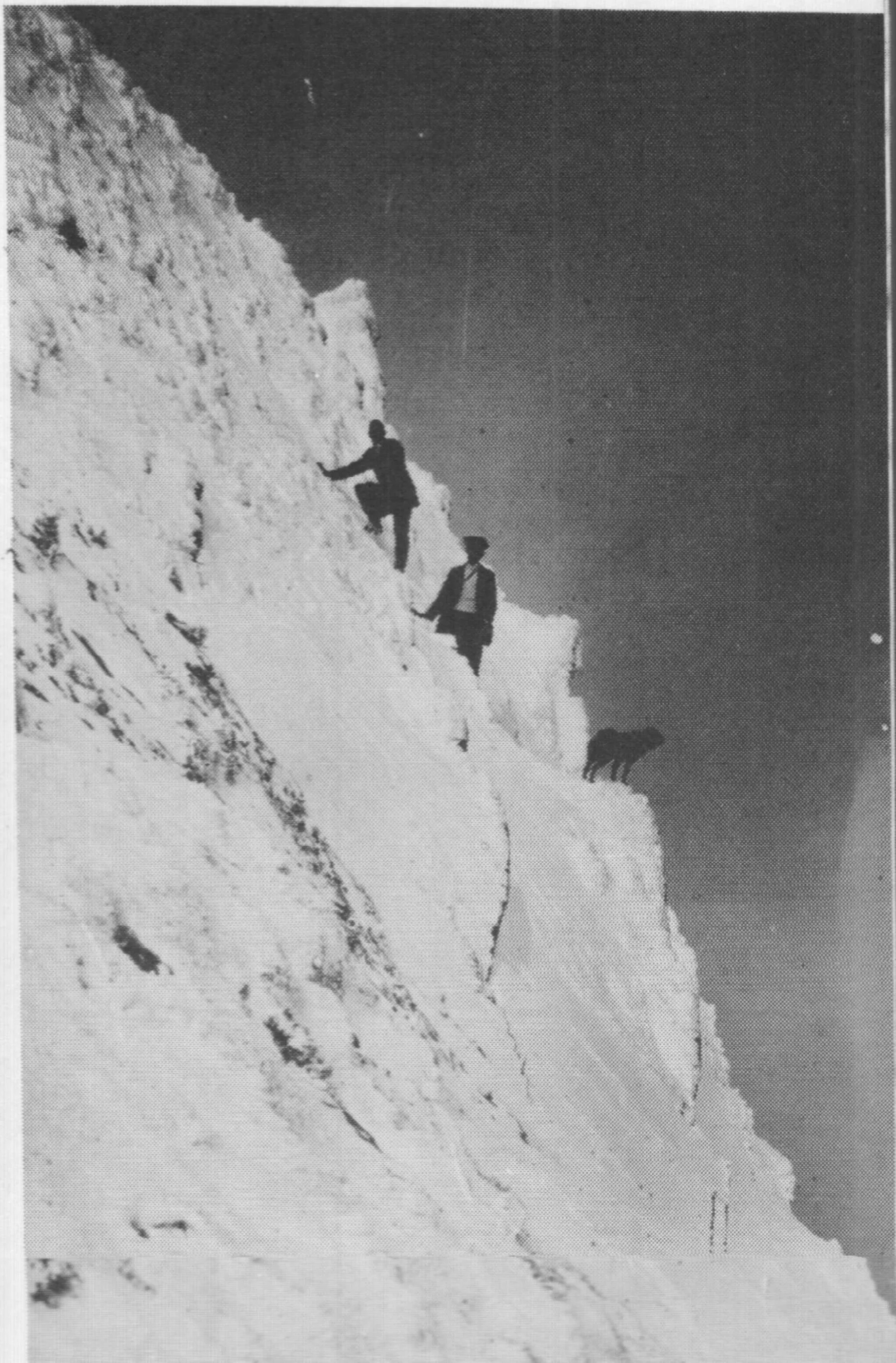

As soon as the railway to Bright was completed, locals began promoting the mountain attractions of the area to capture a share of the lucrative tourist trade. The first winter ascent of Mt Featherop was made by members of the Bright Alpine Club led by A. H. Sharpe and Don Gow in September 1889. They used ropes and wore snow shoes, not crampons or skis.

Climbers and dog. Mt Feathertop 25/8/1911. Photo prob by either R. M. Bowie or Jim Tobias

The first skiing on the Razorback was in either 1900 or 1902 (sources differ) when brothers Harry and Peter Petersen skied from their mine on Mt Tabletop, near the modern town of Dinner Plain, to Harrietville via the Bon Accord Spur. At the southern end of the Razorback, Peter triggered an avalanche when a cornice collapsed beneath him. He was uninjured, but lost a ski and the exhausted brothers arrived at Harrietville well after dark. The first full crossing of the Razorback on skis was by pioneer skier R. W. Wilkinson accompanied by the Norwegian consul, Hans Fey in 1912. They apparently traversed the Razorback from the Great Alpine Road right to the top of Feathertop in just 3 hours, an impressive time even with today's equipment.

In 1906, at the instigation of Jim Tobias and the Harrietville Progress Society, a rough track to the mountain from Harrietville was cut which ran close to the present Bungalow Spur track. A 'shelter shed' was also built near a spring on a flat area near the treeline, but in 1912 it was replaced by Feathertop Hut (see chapter 6). The hut was mainly used as a base for summer excursions, but was occasionally used for climbing and snow walks.

Late in 1919 the nearby Buffalo Chalet was leased by the Norwegian born Hilda Samsing. She put considerable effort into promoting Mt Buffalo as a winter destination and imported skis to hire to guests. This was probably the greatest stimulus that led to the explosion of interest in skiing in the 1920s.

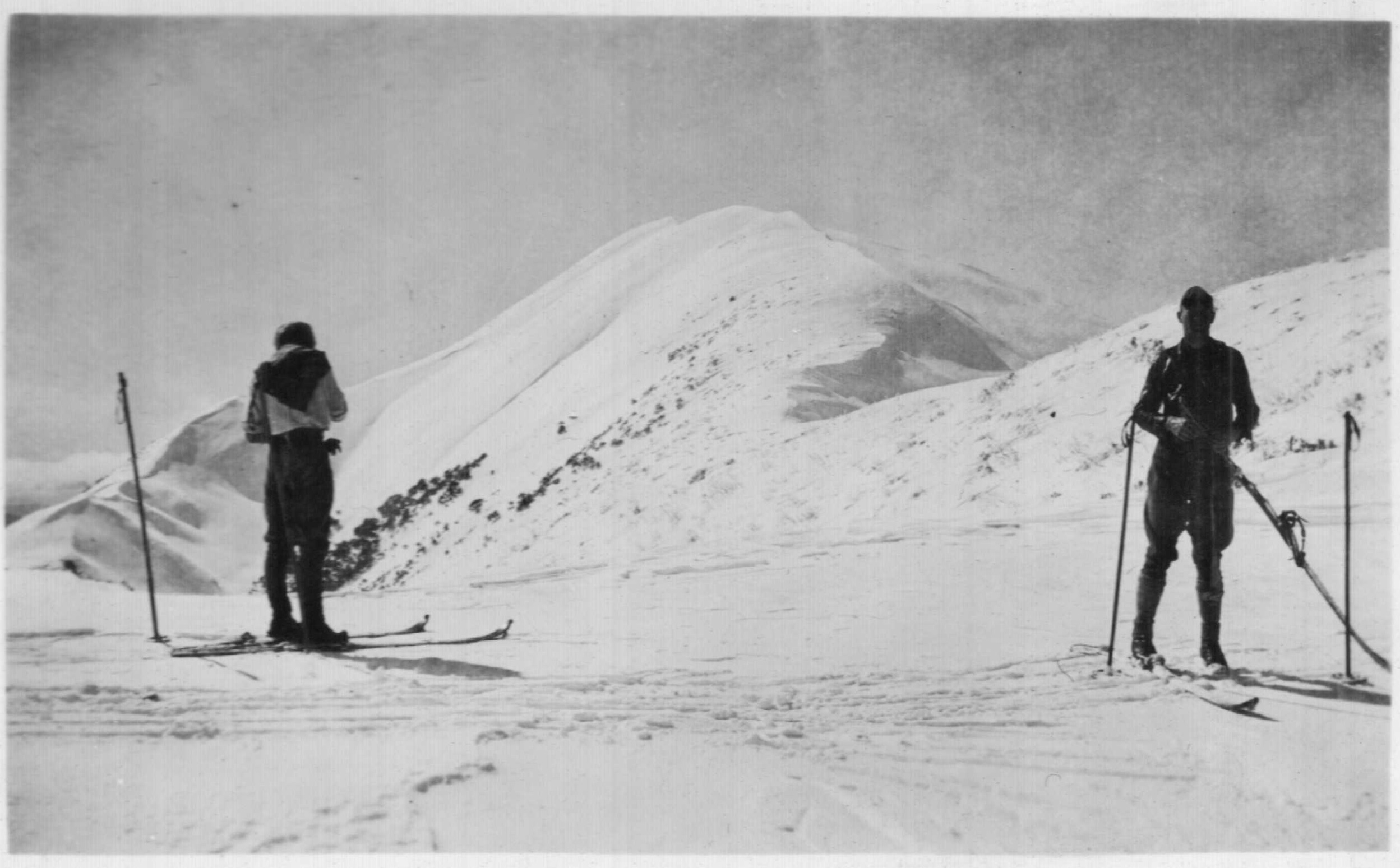

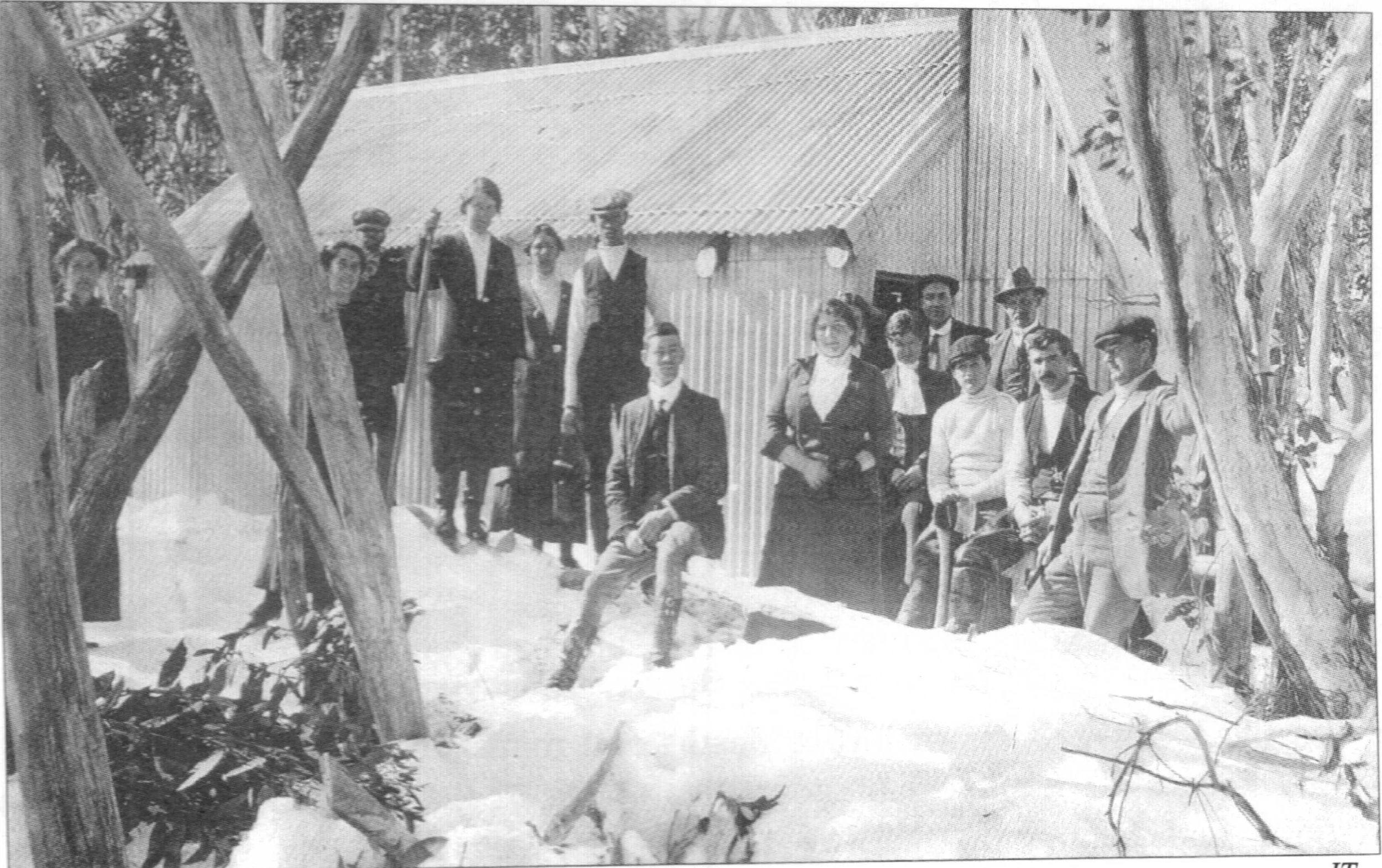

Early skiers on Mt Feathertop, possibly at the 1923 carnival. Photo: Robert Macedon O'Brien. Source State Library of Victoria.

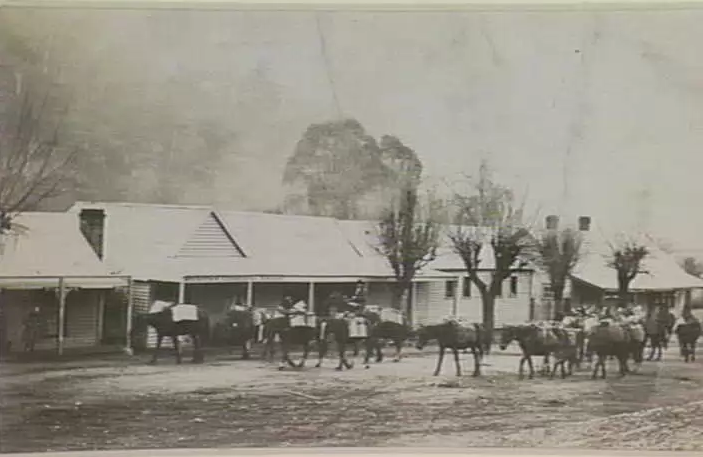

On 10 August 1923, a "Snow Carnival and Ski-ing Championship" was held on Mt Feathertop. On the day 100 horses and 150 pedestrians climbed up from Harrietville.

Organised by the Harrietville and Bright Progress Associations. Ideal day, fine and clear. Over 100 horses and many pedestrians left Harrietville between 7.00 and 8.00 am for the scene of the sports, where every preparation had been made for the comfort of the visitors. The only building on the mount was a shelter shed erected by the Progress Association and consequently visitors had to be content with a picnic in the snow. After partaking of refreshments, a start was made for the skiing ground, where a course of 800 yards had been marked off and flagged. Among the events was a dish race, in which ten starters each sat in a large dish, and one can imagine as they gathered speed, the heat which would be generated by these dishes in their spinning career down the slope. Spills were numerous and seats of trousers suffered...

Sadly, the spectacular sport of dish racing never became as popular as it deserved to be. While Feathertop Hut was the only structure on the mountain, the success of the carnival planted an idea in the minds of some entrepreneurial skiers and a nearby hotel manager who was about to lose her lease.

3. Early days of the Feathertop Bungalow

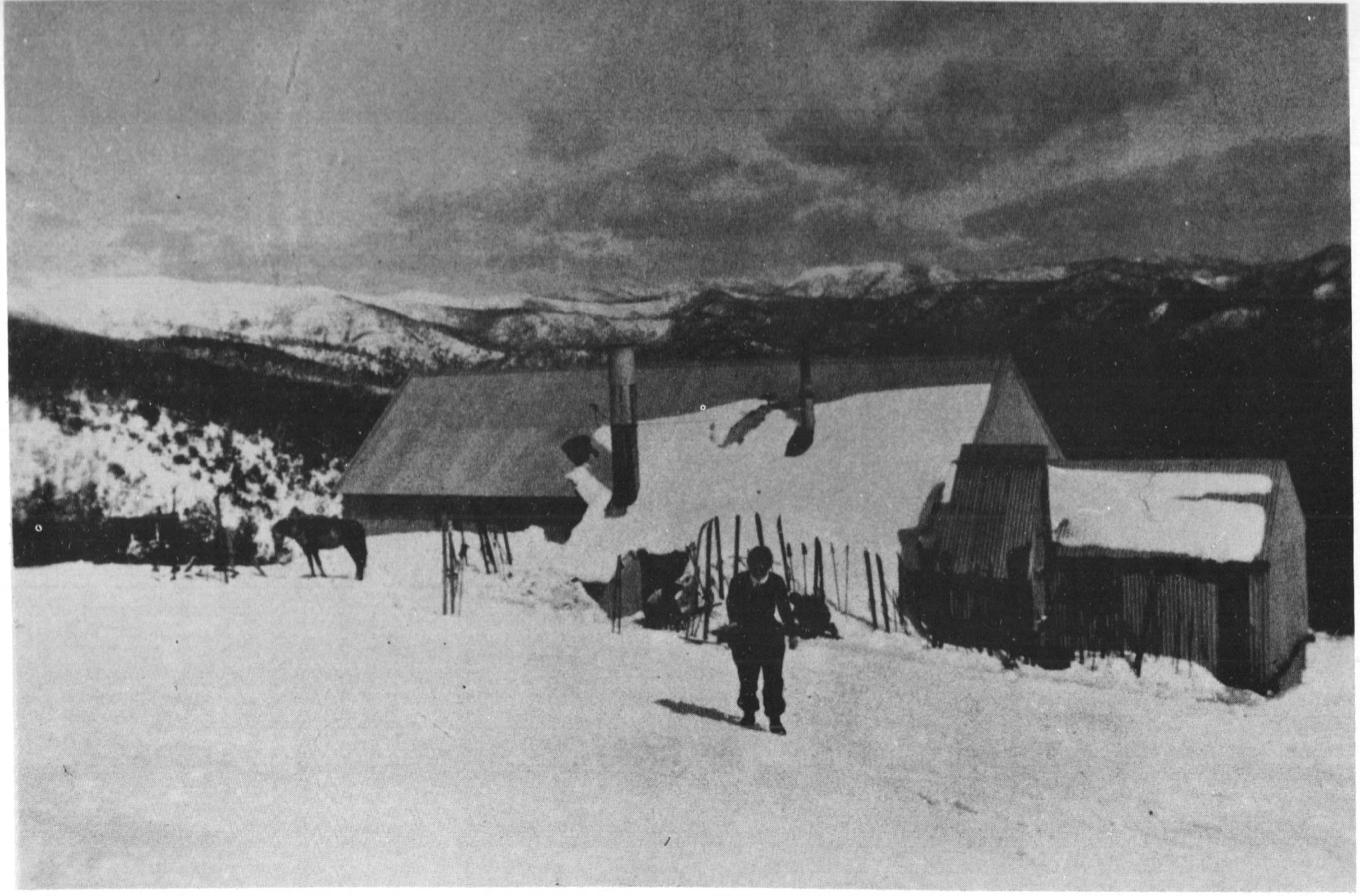

Members of a 'Skyline' package riding tour at the Feathertop Bungalow, circa 1929. Photo: W. Howieson. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Planning and construction

In 1925 the Feathertop Bungalow was built by a syndicate led by Gordon Langridge, one of the pioneers of skiing in Victoria in the years after the First World War. He was in the first group to ski on Mt Buller, was an early skier on the Bogong High Plains and was founding president of three clubs: the Ski Club of Victoria (1924), the Chamois Ski Club (1925) and the Mt Buffalo Alpine Club (1927). In later life he remained a keen skier and in 1947 was involved in establishing the Federation of Victorian Ski Clubs (which became the Victorian Snowsports Association).

Ad for the Buffalo Chalet which appears to be from the time it was run by Hilda Samsing

The other driving force behind the Bungalow was Hilda Samsing. Norwegian born Samsing was a decorated nurse in the First World War and was reputedly the only woman to go ashore during the Gallipoli campaign.* On her return to Australia, she held the lease of the Buffalo Chalet from 1919 to 1924 for a fee of £800 per year. The Buffalo Chalet had become run down under the former management and complaints about the standard of accommodation were not unusual. So Samsing thoroughly renovated the building, installed new furniture and began to promote it as both a summer and winter destination. Occupancy soon took off and the Chalet became rather profitable. But perhaps she was too good at her job because in late 1924 she lost the lease to the Victorian Railways, who took over as the new landlords of the Buffalo Chalet. Samsing was compensated £4863 for the 'plant and equipment' she left behind at Buffalo. She was keen to stay in the ski accommodation industry and readily accepted Langridge's approach for her to join the syndicate. According to The Herald, she took a break in Europe in early 1925 and had a look at snow tourism on the Continent.

There are two other women who may have gone ashore at Gallipoli, both to possibly visit the grave of Lt Col Charles Doughty-Wylie VC. One was his wife Lilian Doughty-Wylie, a nurse and philanthropist, the other was his friend and possible lover Gertrude Bell, a well known anthropologist and diplomat.

Bungalow co-founder Hilda Samsing as a nurse in the First World War.

The Feathertop Bungalow was intended to be a minor forerunner of a huge project over ten times larger. It was to include a 300 bed chalet and international standard ski jump, for a total cost of £80,000, an enormous sum for the time and if capital could be raised,it was hoped to commence building in the summer of 1925 - 1926. The syndicate was planning a complex much bigger and better than the Buffalo Chalet with a road, walking tracks and extensive ski runs. The railways were reported as welcoming the planned project but they would hardly have declared that they would do their utmost to to squash this new competition; but more on this later. If the full proposal had gone ahead, it is probable that Feathertop would have developed into Australia’s premier ski mountain.

So with the most enthusiastic skier and the most dynamic ski industry business person of the day on the board, the company looked well placed to thrive in the rapidly growing new sport. The first visible action of the nascent company was to upgrade the rough walking track from Harrietville up what would become known as Bungalow Spur to a well graded pack-horse bridle track to allow building materials to be delivered. By the 1930s the track was being used by oversnow tractors.

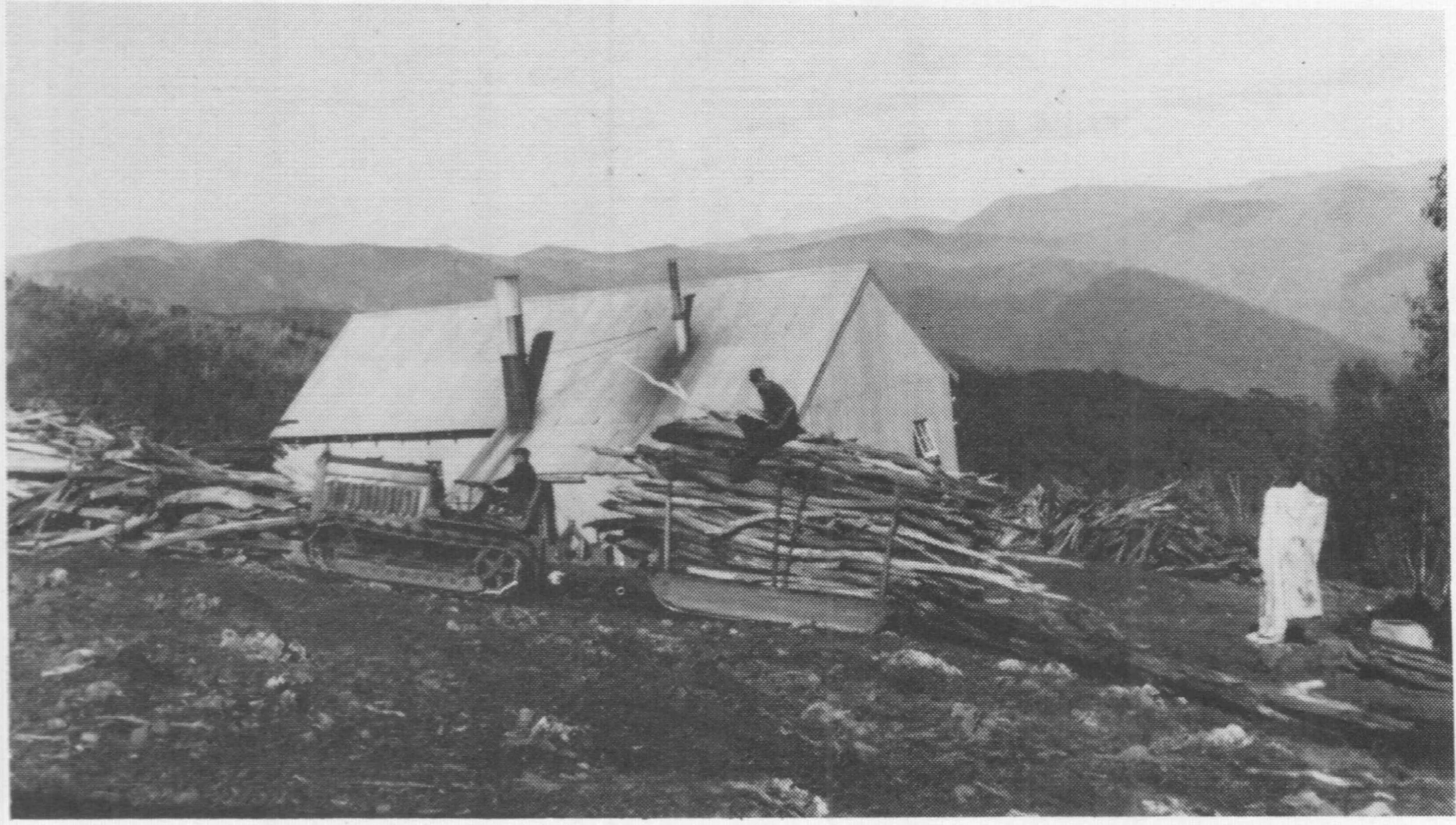

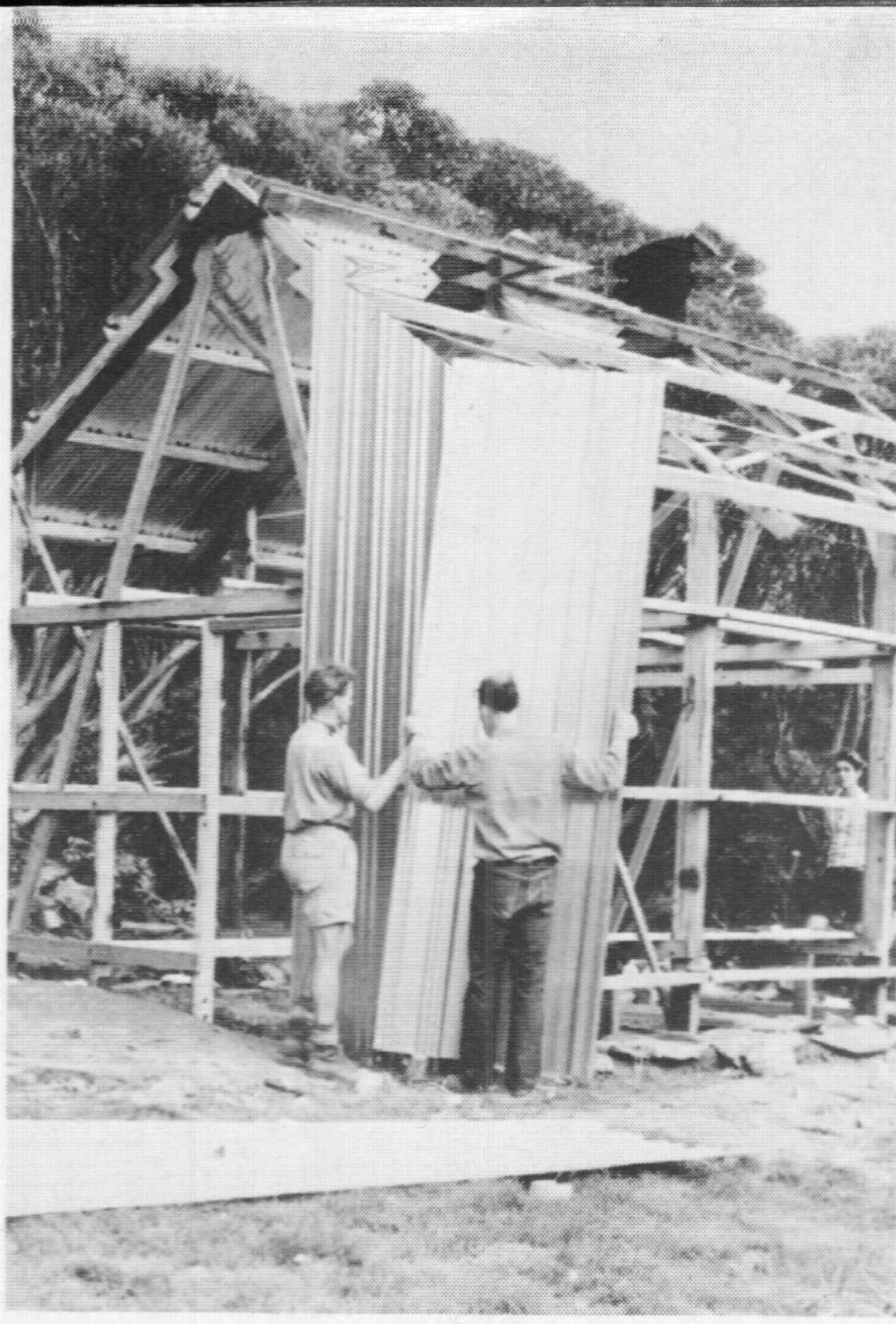

The Bungalow was prefabricated in Malvern Road, Prahran by Davies & Co. and transported by train from Malvern station to Bright and then by road to Harrietville. Six sleds, each pulled by six horses, moved the sections from Harrietville to the building site where it took three weeks for seven carpenters, two plumbers and six labourers to erect it. Tor Holth interviewed mountain cattleman Billy Howard on his experience of transporting corrugated iron to the Bungalow on pack horses. '[there were] about seven to eight foot sheets and we rolled them in a half moon with straps around and they went up over the horses neck and just about, scratched the ground. I used to do two trips a day. I had two packhorses. My father had the sleigh and he'd be flat out doing one - he had a heck of a job. It was a well-made sleigh with two runners. It was five miles and a reasonably good track.'

The outside walls of the Bungalow were utilitarian corrugated iron while the inside was lined with tongue in groove wood. There were eight bedrooms with four beds in each, (although later the bunks were removed from some rooms and were replaced with two single beds). The Bungalow also had a large dining and lounge room equipped with a gramophone, two bathrooms and a kitchen. The building featured electric lighting and while hot water was not provided initially, a hot water service was installed later to replace the need to heat bath water on the stove. However the Bungalow didn't have a septic tank and two outdoor toilets were positioned on the edge of a cliff above an understandably fertile valley.

Feathertop Bungalow without the northern annexe. Photo from Matt Guggisberg's site.

Opening and operation

After fit out and delivery of 50 pairs of Norwegian skis, the Feathertop Bungalow opened for business on 13th July 1925 with a display of fireworks in the evening. The total cost was £3,000. It is impossible to provide a relative price in today's money, but the original Buffalo Chalet (before extensions) had cost £7,000 when it was built 15 years earlier.

The Feathertop Bungalow in summer. Photo: Harrietville Historical Society.

The Bungalow was well patronised and popular, members of several ski clubs including the Ski Club of Victoria regularly stayed there, (despite an apparent dispute Langridge had with the SCV which had led to him resigning his presidency and establishing Chamois Ski Club). At least one school hired the Bungalow as it is recorded that 20 Scotch College boys stayed there in August 1927. Hilda Samsing was the resident manager in winter, while a caretaker looked after the building and guests in summer. Samsing's widowed sister in law, Hannah Samsing dealt with the accounts.

Difficulties with land tenure

The Bungalow was built on Crown land but the owners had gambled on speeding up construction by building on a miner's right, rather than waiting for approval from the Lands Department for a long term lease or waiting even longer to buy the land. During the later years of the gold rush, it became fairly common practice for people wishing to settle in an area to peg residential sites under a miner's right rather than wait for the slow moving bureaucracy to grant a more permanent form of tenure. While this loophole still existed 60 years later, by the 1920s it was rarely used and easily revoked, especially if the residents made no attempt to mine the land.

It appears that the syndicate were confident that they would get tenure of their land without much difficulty. But the Lands Department delayed making a decision and decided to consult widely on the issue. Langridge later wrote that he believed certain bureaucrats deliberately obstructed the owners of the Bungalow in their attempts to obtain a 50 year lease. The railways, who were now the operators of the Buffalo Chalet, had forced the other two accommodation houses on the Buffalo Plateau to close and also did their best to thwart this new competitor. One of their tactics was to argue that this previously unknown mountain was a tourist area, so any developments should be built to a high standard and if the rather basic Bungalow wasn't upgraded within seven years, the railways should have the option to take it over. The Minister of Lands, (either A. Downward or H. S. Bailey) reportedly disagreed with the railways, seeing their proposal as far too restrictive and it appears he favoured granting a 21 year lease. And thus the status of the Bungalow became stuck in bureaucratic limbo with the railways having the influence to block any proposed resolution.

By late 1927 it became obvious that no lease would be granted and the owners salvaged what they could by selling the profitable Bungalow to the railways in June 1928 for a bargain £250, only 8% of what it had cost to build. (Although one source says the sale price was £450.)

There are interesting parallels between the Feathertop Bungalow and the Buller Chalet as they were very similar projects. The Buller Chalet was built in 1929 by a syndicate of skiers and Mansfield people. It only slept 14 when first built, but had grown to accommodate over five times that number within a decade. At a time when few people owned cars, both the Bungalow and the Buller Chalet were a similar distance from a rail head and both were accessed by road and then a well graded bridle track. Both had similar facilities. Of course after the experience of the Bungalow's land tenure, the builders of the Buller Chalet made sure they had a secure lease on their land. Despite the economic hardship of the Great Depression, the Buller Chalet was a huge success and was extended to 32 beds in 1932 and between 67 and 80 beds in 1939 (sources differ on its final capacity). It escaped the 1939 fires, but was destroyed in 1942 when a burning log spilled out of an unattended fireplace. It is interesting to speculate if Mt Feathertop would have developed in the same way as Mt Buller if the visionaries who built the Bungalow had managed to get a secure lease or to buy the land.

The Ladies Slalom Course off Little Feathertop in 1937. Federation Hut is now at the base of the hill in the centre of the picture. Photo by Gerard Wardell. Source: State Library of Victoria

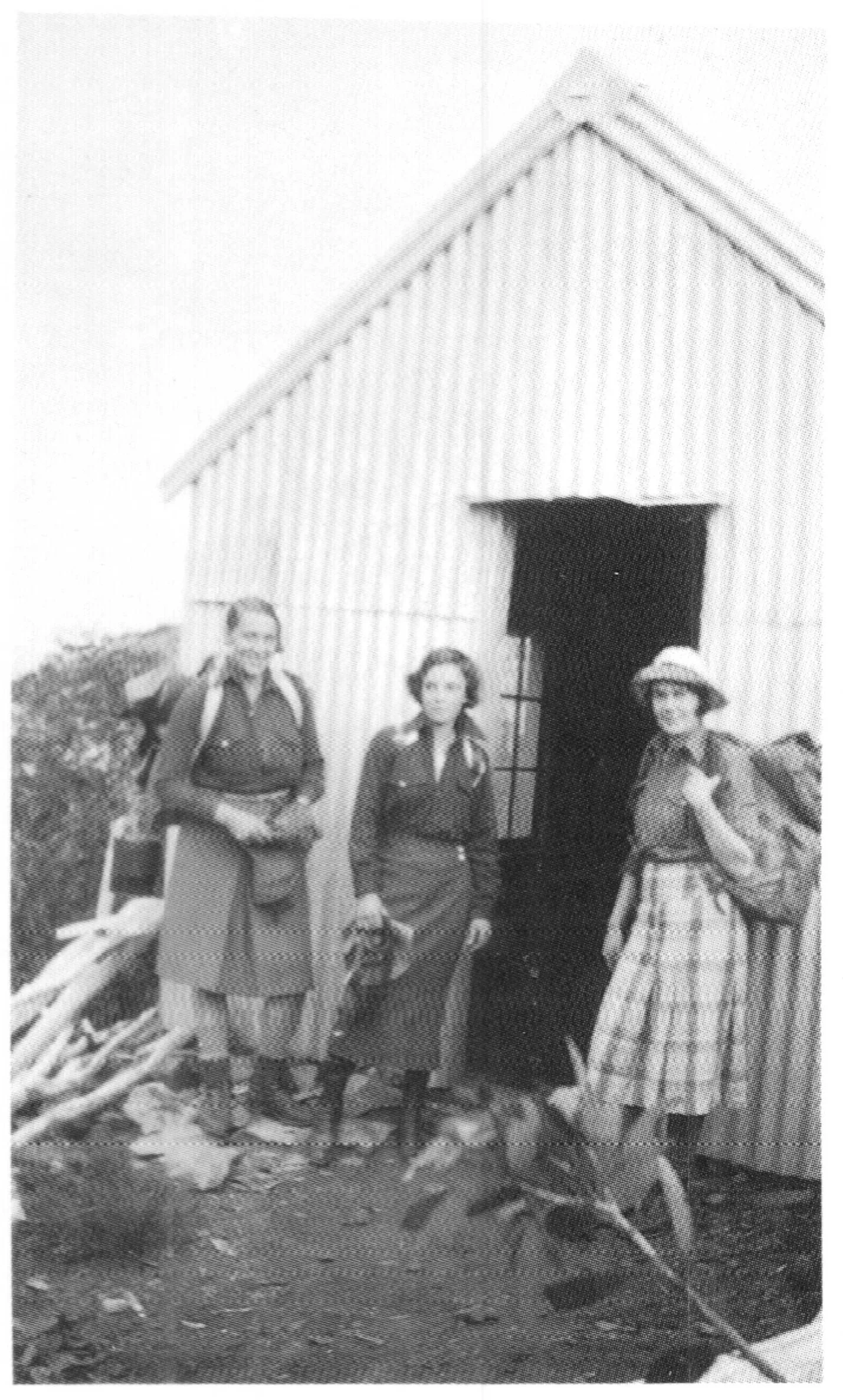

Marjorie Good (later Leviny) and friend at the Bungalow before embarking with Kit Moore on the first women's winter crossing of the Razorback from Feathertop to Hotham Heights.

Photo Harrietville Museum.

4. The last decade of the Bungalow

Before the railways realised the potential of the Bungalow and appointed a manager, conditions were more basic than they had been earlier. There had been controversy when Harold Clapp, the railways' commissioner, had bought the Bungalow, despite opposition from senior figures in the railways and state government, so things may have been deliberately kept low key until the fuss died down. It's unclear how actively the railways managed their new acquisition during the first two years of their ownership, but ski groups are recorded staying there 1928. Experienced ski tourer Marjorie Good (later Leviny) reported that conditions at the Bungalow in the 1929 ski season were 'terribly, terribly rough'.

This decline of the Bungalow was soon reversed. From 1930 to 1934 Ada Banks was employed as manager for a generous £7 a week. This was almost double the average wage at the time, so the £7 may have included allowances for other operational expenses such as laundry. Her duties included riding up to the Bungalow to deliver perishables such as meat, cleaning it prior to guests arrival and cooking for them during their stay.

In later years the Bungalow was staffed in winter and peak summer periods. Groups such as the Wangaratta Ski Club and the University Ski Club often hired the entire Bungalow for a week and contrary to some published claims that the Bungalow was abandoned, it was usually full in winter and got plenty of business in summer.

Managers of the Bungalow when it was owned by the railways were: Ada Banks 1930 - 1934, Jim and Pearl Bradshaw 1935 - 1936, Mr and Mrs H. Richards 1937 - 1938, Mr and Mrs Marshall 1938 - 1939. In addition, the railways employed Alf Rosner for a year in some role at the Bungalow in the late 1920's possibly as a cook or a handyman.

The Feathertop Bungalow in 1931. Photo Alan Brockhoff.

After managing the Feathertop Bungalow for two years, Jim and Pearl Bradshaw moved to Hotham Heights which the railways had recently acquired. They successfully managed it from 1937 to 1946, seeing it rebuilt after the 1939 fires and running it through the Second World War. They got on well with Bill Spargo, the former lessee of Hotham Heights, who became a full time prospector, hiring him for occasional work to supplement his modest mining income. To everyone's surprise, Spargo eventually discovered a rich gold deposit near Hotham and the Red Robin mine made the impoverished prospector a wealthy man.

Strip ticket for a package of transport and accommodation at Harrietville Museum. Photo Ronice Goebel.

A newspaper article infers that Spargo gave Jim Bradshaw a share of the claim: 'I advised Mt Bradshaw... to take a share. He had been a good neighbour to me, and my chance came to do him a good turn.' However Stephen Whiteside, who interviewed Pearl Bradshaw in 1987 and 1988 says that Pearl asserted they never made any money from the Red Robin and he believes that instead Spargo may have given Jim Bradshaw the nearby One Alone mine which Spargo had worked sporadically but which never paid more than expenses. In any case, after 12 years of running isolated ski lodges, in 1947 the Bradshaws had the money to acquire a servo in South Melbourne before changing to a cafe a few years later. They were probably the only people associated with the Bungalow to do well financially from running ski lodges.

When the railways took over the lease of the Buffalo Chalet, they bought some of their corporate culture with them. One aspect of that was the use of tickets for activities, ski hire, transport and accommodation. After they acquired the Feathertop Bungalow and began to take it seriously, the use of tickets was also introduced there. The photo shows a strip ticket with detachable coupons for a package deal of accommodation and three modes of transport. While it appears that most of the railways package deals for transport and accommodation at the Bungalow included first class rail travel, the accommodation wasn’t close to first class standards, even by the modest standards of the 1930s.

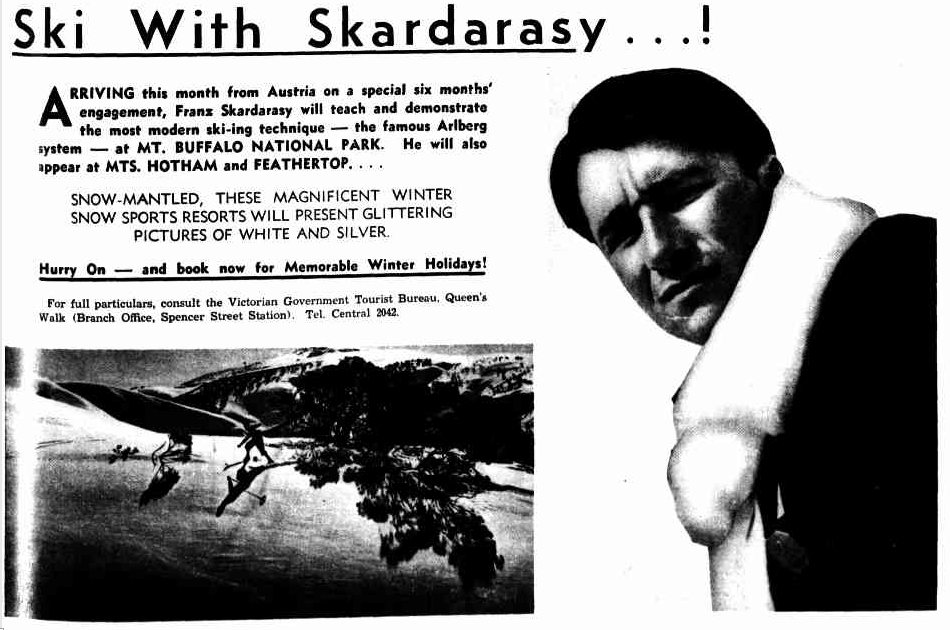

As the 1930s progressed, the railways gradually improved services. From 1936, Eric Stewart was employed by the railways as a 'snowline representative' to escort guests to Hotham Heights and the Feathertop Bungalow. In 1936 the Austrian ski instructor Franz Skardarasy taught at Feathertop and Hotham, although his main base was at Buffalo. By the late 1930s ski instructors were based at all three of the railways' ski lodges. The Buffalo Chalet and Hotham Heights got Austrian instructors, but guests at the Feathertop Bungalow had to make do with a local. The 1939 Ski Yearbook reported that Freddie Pryce Jones was the Feathertop ski instructor in 1938.

Under the control of the railways, Feathertop was mainly marketed to intermediate skiers, those who had graduated beyond what was available at Mt Buffalo or Donna Buang, but who were not ready for Mt Hotham which was difficult to access in winter and sold as a ski destination for experts. Typical of the coverage Mt Feathertop received is this extract from a long article on skiing in Victoria published in the weekly social newspaper Table Talk.

Feathertop Good for the Tyro

FEATHERTOP is attractive to beginners as the bungalow is built about four miles above Harrietville, and it is a pleasant walk up the timbered track—especially if you are wise enough to put your skis and pack on a horse. There are gentle slopes close to the Bungalow where the learner can find his ski legs. Then after a few days practice there is a pleasant trip to Mt. Feathertop, about a mile away, and the hours will go quickly as you negotiate the steeper slopes at the foot of the mountain. Table Talk. 11 June 1936. pp. 16 - 17.

Sign at Wangaratta station listing three branch lines in the area and showing the railways three ski lodges in the pre war years. The railways did not control the St Bernard Hospice and it is absent from the list. Photo: © Peter Dwyer. Used with permission.

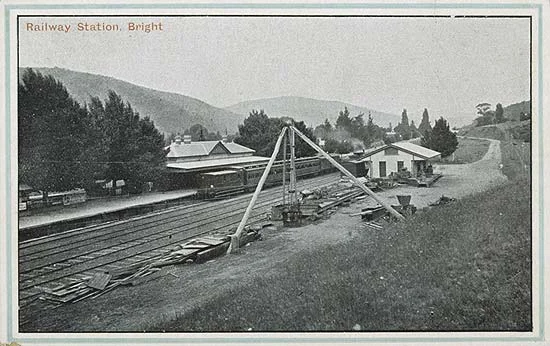

Transport

After many delays the railway to Bright opened in 1890. A rough survey was done for an extension to Harrietville with the terminus planned to be behind the school. But the economic depression of the 1890s put an end to any hopes of the line heading further up the Ovens Valley, so Bright remained the railhead for the area until the line closed in 1983.

When the Razorback hosted gold mines in the late 19th century, huge machinery such as steam engine boilers, stamping batteries and water wheels were somehow dragged up the slopes of Mt Feathertop on drays drawn by bullocks or horses. Teamsters such as George Sealey used pulleys and winches to assist their animals in hauling machinery and supplies up to the Razorback and Champion mines.

The 20th century saw tourism take over as the main activity on Mt Feathertop. In the 1920s and 30s many main roads were still gravel and by today's standards, cars were uncomfortable and unreliable. So most visitors to Feathertop caught the train along the Ovens Valley to the terminus at Bright where they transferred to hire cars for the final part of the journey to Harrietville.

By 1937 express trains on the north east main line from Melbourne to Albury traveled at much the same speed as they do today. But other trains stopped more frequently and were much slower, especially trains on lightly built branch lines. So most travel was at a far more 'leisurely' pace than today. Roads were poor, cars often unreliable and there was no real competition from airlines, thus there was no great pressure for the railways to speed things up.

Bright railway station in the 1920s. It was here where guests bound for the Feathertop Bungalow transfered to cars for the trip to Harrietville.

In the 1930s guests staying at the Bungalow would usually leave Melbourne at 4.00 pm on Friday, take dinner at the Wangaratta station refreshment rooms before departing on the Bright 'mixed' train (which hauled passenger and freight carriages) at 8.30 pm, arriving at Bright after 10.00 pm. They would either stay the night at Bright or travel to Harrietville by road before ascending Bungalow Spur on Saturday morning. On other days, an 8.00 am departure from Melbourne was required in order to connect with the daily mixed train which departed Wangaratta at 1.00 pm. After shunting trucks at intermediate stations, the train arrived at Bright at 3.15 in the afternoon.

A pack horse being unloaded by Frank Wraith near the Bungalow. Jim Bradshaw, manager of the Bungalow is at the back.

From Harrietville guests headed for Feathertop took the bridle track built in early 1925 to transport construction material for the Bungalow. They had a choice of walking or hiring a horse for 5/-, but most chose a middle option of walking and using a pack horse to carry their luggage. In light snow the horses could get all the way to the Bungalow, but in heavier conditions they were unloaded lower down the mountain. After the horses were unloaded, their reins were tied and they found their own way back to Harrietville.

Kath Magill and friend at the Bungalow. August 1936.

The end of the Bungalow did not mean the end of the pack horse on Feathertop and in the 1940s Eric Johnson Gravbrot packed supplies for visitors staying at Feathertop Hut.

While the track was gradually widened and improved to allow oversnow tractors to reach the Bungalow, it was never a true road. At the time roads were built with steam powered excavators, horse drawn dirt scoops and a great deal of manual labour, so building mountain roads was especially expensive. This changed in 1938 when the Kiewa Hydro Electric Scheme used the first bulldozer in Victoria to build the road from Tawonga in the Kiewa Valley up to the Bogong High Plains. While the advent of bulldozers made building mountain roads more affordable, the loss of the Bungalow in January 1939 and the outbreak of the Second World War seven months later, meant that any dreams of a road up Feathertop were never realised.

After the war many 4WD roads were built in the high country, but except for a few fire access tracks, roads were always built to serve an economic purpose such as hydro electricity, timber harvesting or tourism. In 1954 the Bright Shire was pressing for a road to be built on Mt Feathertop, but they were apparently looking for finance from state government authorities and it is unlikely they had the money to build it themselves.

While a few logging roads were built lower on the mountain, there was no reason to extend them beyond the middle slopes. In the 1970s some alarmist stories were put out about proposed roads along the (southern) Razorback or up Bungalow Spur, but it appears that constructing them was never seriously considered. The cost couldn't be justified as the Bungalow was long gone and very few stands of timber would be accessible from roads on those routes. To practical country people such as the cash-strapped local shire and logging contractors, it didn't require an elaborate cost-benefit study to determine that such roads wouldn't be of much use to the locals, nor would a road on Feathertop earn much income for whoever built it.

Cletrac oversnow tractor at the Bungalow. Similar machines worked at the Buffalo Chalet. Photo: Harrietville Historical Society.

Undated photo of Cletrac tractor hauling firewood to the Bungalow without the north wing

Skiing

There was some clearing of ski runs on Feathertop and as the railways began to realise the potential of the Bungalow and the mountain, a few more ski runs were cut in 1934, but the treeline was a little lower in those days. No ski lifts were ever built, although the Wangaratta Ski Club built a ski jump in 1938. As it had easier access, many skiers before the Second World War considered Feathertop more suited to intermediate skiers with Hotham better suited to experts due to the perilous crossing from Mt St Bernard along the Great Alpine Road where no attempts were made to clear the road of snow until 1957.

In the pre war years there were over 20 active ski clubs in Victoria and many held races on Feathertop, including the 1929 Ski Club of Victoria championships and a number of Wangaratta Ski Club contests, although the mountain never hosted the national championships. Before 1955, it was impossible to actually hold proper state championships as one larger club, the Ski Club of Victoria, refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of other ski clubs and would not race against their members.

Two photos show an apparently smaller Bungalow without the northern section, my guess is that this wing was probably a storeroom with accommodation for staff. It is not known if this was part of the original building or added later and I have not found any written material on the subject.

Ski runs below the treeline on Bungalow Spur 1934. Photo K. Magill.

It is possible that the building may have been built with the northern wing, which was later demolished, or that it was an extension added to the original building at a later time. Two photos dated 1929 and 1935 show the northern wing, so modification to the building must have happened in either the first four or last four years of its existence. The presence of a Cletrac tractor in one of those photos without the northern wing suggests that the extension or demolition took place after the railways assumed ownership as they also ran Cletracs at Mt Buffalo from the late 1920s to the 1940s and it would have been fairly easy to transfer one to Feathertop.

Destruction

The Black Friday Fires of 13 January 1939 were the biggest the state has ever seen and consumed Razorback Hut, the first Bon Accord Hut, and the Bungalow. The old Feathertop Hut was spared.

Feathertop from The Playground. 1934 Photo Kath Magill.

No Bungalow for Feathertop!

Feathertop seems to have been temporarily eclipsed as a ski-ing resort. The railways have no intention of re-building the Bungalow there, burnt in the January 1939, bush-fires, and do not intend to play any part in the future development of Feathertop.

The Bungalow there was always a popular place for beginners and those not so well-equipped by nature for the longer trip to Hotham, The well-graded track from Harrietville is easy to follow, protected all the way and horses could reach the Bungalow in all but exceptional conditions, a feature especially attractive to the uninitiated and one which also eliminated the need for packing in a good deal of the food supply in preserved form during the summer, and sledging fresh meat during the winter. [This was how lodges at Mt Hotham were provisioned from 1925 to 1958.]

The Feathertop Bungalow site in 2005. Photo: © David Sisson.

Slopes are better than at St. Bernard, both for beginners and for those more advanced. Here is an opportunity for the S.C.V. or Wangaratta S.C. to make more liveable the present hut near the Bungalow site, with the permission of the owners, the Harrietville Progress Association. Better still would be to re-build it nearer Little Feathertop, where there are some good southern slopes. There will always be a demand for such a hut, as without it the Razorback trip is not safe. The future may give it additional uses, as Tony Walch was keen to try the slopes of Big Feathertop for late spring ski-ing. The present hut has bunks for six.

Despite a recommendation from the S.C.V., the State Tourist Committee has not yet seen fit to put a pole-line across the Razorback from Feathertop to Bon Accord. Except [for] the Fainter traverse, this is the last remaining high-level route which is used frequently enough to warrant such expenditure, and it is to be hoped that something will be done as soon as the war is over. The trip can be a delightful one on a good day, but the route is very susceptible to fogs and sudden changes of weather, and the loss of the half-way hut (1939 bush-fires) renders the trip doubly difficult in these conditions.

Australian and New Zealand Ski Year Book 1941. p. 52.

The outbreak of the Second World War, seven months after the Bungalow was burnt prevented any reconstruction, but in 1946 the Wangaratta Ski Club took out a permissive occupancy lease on the site of the Bungalow with a view to building a lodge on Feathertop to complement their new (1946) lodge near Mt St Bernard. They were still considering building on the site in 1956, but let this option lapse some time later. This was the last realistic chance to reconstruct the Bungalow. Sadly, rebuilding the Bungalow would be 'politically impossible' today, too many people would find too many reasons to object.

Between 1925 and 1932 the Victorian Railways took over three ski lodges in the Bright area from previous operators and often promoted them together. Mt Buffalo Chalet. the largest and most comfortable, was marketed as suitable for novices, the Feathertop Bungalow for intermediate skiers and Hotham Heights was sold as a destination for experts. Staff such as Skardarasy were sometimes shifted between locations over the winter. Advertisement from Table Talk. 4 June 1936. p. 31.

Signpost to Hotham – approach to Feathertop summit. located where the Razorback meets Bungalow Spur. Photo W. H. Jemison, October 1950. © High Country Online. Used with permission.

5. Post war events and proposals

Feathertop is overtaken by other ski destinations

After the war ended in 1945, lodges were quickly built at Mt Buller and Mt Hotham which began to develop into modern ski resorts. They were joined by Falls Creek in the late 1940s and Baw Baw in the early 1960s. While Mt Buffalo trundled along under railways management without much change until the mid 1960s, two pre war ski destinations were eclipsed. One was Donna Buang, Victoria's busiest ski resort before the war. From the late 1940s its popularity shrank rapidly and it had been completely deserted by skiers by 1953.

Mt Feathertop was the second ski destination to disappear from the awareness of skiers. By 1950 there were two dozen lodges either built or under construction at Buller while Hotham had five lodges, two ski huts and another lodge nearby at Mt St Bernard. Falls Creek had four lodges with many more planned. This post war explosion of activity consumed the attention of skiers and the new ski lodges provided comfortable bases for skiers to explore nearby mountains. But without the Bungalow or anything other than an increasingly run down hut, Mt Feathertop could not compete effectively for the attention of skiers.

The October 1951 issue of Ski Horizon magazine has a glowing report on skiing on Mt Feathertop, but the author was amazed that during the whole ski season of that year, just two groups had booked Feathertop Hut, the only surviving building on the mountain. That article appears to be the last that treated Feathertop as a mainstream ski destination, from then on it seems to have been viewed as just another remote mountain only visited by backcountry skiers, climbers and hikers.

Hikers on Feathertop, spring 1962. © Margaret King. Used with permission

Tracks and management

Walking track development

In the 1930s, after the mining tracks became overgrown. the only properly built track on the mountain was the track to the Feathertop Bungalow, although generations of mountain cattlemen droving cattle along the full length of The Razorback from Stony Tops to Mt Hotham had created a cattle-pad on that route. It seems there was also a foot-pad up Diamantina Spur in the 1930s. Work was begun on a track up North West Spur in 1965 by the Melbourne University Mountaineering Club during planning for their hut. However track building on the spur was suspended when the access route for hut construction was shifted to the old droving route along the North Razorback, with the North West Spur track finally being completed in the late 1960s.

While snow pole lines were installed on the Bogong High Plains and Mt Hotham during the mining era of the late 19th century and renewed for skiers and hikers in the 1920s and 30s, it appears that no snow pole lines were ever built on Feathertop or the Razorback, despite lobbying by skiers in the years before and after the Second World War.

In recent decades Parks Victoria has upgraded some of the old foot-pads and cattle-pads, notably the southern approach to the summit. But in line with their apparent 'all or nothing' approach, some routes such as the (southern) Razorback track from the Great Alpine Road to the summit have been 'gold plated', while others have had little work done on them and remain fairly rough and often difficult to follow.

In 2016 Parks Victoria launched a proposal for a new walking route from Falls Creek to Hotham taking five days rather the usual long single day. The 'Falls to Hotham Alpine Crossing' would charge fees to walkers and is a much less direct route than the present one. It diverts off the High Plains via Lake Spur, the West Kiewa River and Diamantina Spur before ascending Feathertop and arriving at Hotham via the Razorback. If the proposed track is built, it will involve a major upgrade of the fairly rough track on Diamantina Spur. However with an enormous price of $34.1 million for the full project, including $1.444 million to upgrade the track on Diamantina Spur, it is hard to see how it could be completed in the foreseeable future. The 116 page final plan was released in 2018.

1928 map showing snow pole lines. Many maps used by skiers were this basic. Source SLV.

Management

As a former mining area, Mt Feathertop was administered by the Lands Department from its creation in 1919. In 1962 the Lands Department established the Mt Hotham Committee of Management to manage the nearby ski resort. As it was a former ski destination close to Hotham, most of Mt Feathertop was included in the resort boundaries. While Hotham administered the mountain, it was never seriously considered for development, although the resort did issue 'permissive occupancy' leases for two refuge huts in the 1960s.

In 1981 the mountain was included in the newly created Bogong National Park. In 1989 Bogong National Park, two other existing parks and the surrounds of the Dartmouth Dam were joined by thin strips of snowgum woodland to become the Alpine National Park.

The Cross in 1997. It was located near the junction of the Razorback track and the track to Federation Hut. Photo © Terry Linsell from his website. Used with permission.

The Cross

In the latter part of the 20th century there was a cross made of steel tubing on the track below the saddle between Molly Hill and Little Feathertop. Because a few older maps referred to it as a 'Memorial Cross', some people assumed it was erected in memory of skiers who fell in the Second World War.

The oldest reference to it that I had found was in a 1963 trip report reproduced in the Victorian Mountain Tramping Club history, but Thomas Whiteside, a fellow mountain history writer, offered to find out more. Early photos, such as the one in the MUMC Hut section, show a figure of Christ attached to the cross which pointed to a possible Roman Catholic connection, so he contacted the Catholic Walking Club and the club secretary, Bernadette Madden, replied:

Prior to Easter 1957 a few members of the club formed a group called 'The Alpine and Wayside Cross Society'. The group included William Gleeson who was a professional artist and print maker. He was asked to design and have cast in solid aluminium the figure of Jesus Christ fixed to a metal cross. This was funded by the group and their friends and was not an official club activity... Eventually the metal figure succumbed to the freezing conditions...

The aluminium figure had disintegrated by the 1980s and the cross seems to have disappeared around the turn of the 21st century, possibly destroyed in the 2003 fires or removed by hard line environmentalists.

Three development proposals

Hydro electric plans

In 1947 plans were revised for the partly built Kiewa Hydro Electric Scheme centred on the nearby Bogong High Plains. The new plan envisioned a much bigger project to that planned in 1938 when work began, including hundreds of kilometres of concrete lined aqueducts, most with parallel tramways, to divert extra water from nearby streams into the upper Kiewa River catchment.

One of these aqueducts was to cut across the precipitous east face of Feathertop, diverting water to flow southwards to Cobungra Gap (the divide between the watersheds of the Cobungra and West Kiewa rivers) at 1380 metres before turning north and flowing along the western fall of the Bogong High Plains, across Lake Spur below Weston's Hut, to feed an underground power station located north of The Fainters. A map of another proposal shows a lower aqueduct at 1100 metres which is not far above the West Kiewa River to the east of the mountain and it appears the final plan was to build this lower aqueduct.

Bogomg Creek Aqueduct and tram line with Mt Bogong in the background, A similar aqueduct was planned for the east face of Feathertop.

Work was well advanced on the expanded project when the 1952 credit crunch hit. The federal government's Loans Council imposed severe limits on all government borrowing and state government projects across the country were either canceled or wound back. What money was available for water related projects was directed to the Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme, the Upper Yarra Dam and rebuilding Eildon Dam which had an unstable wall. The Kiewa scheme was shrunk radically to only a little larger than the original 1938 plans. Bogong Creek Aqueduct was the only raceline completed to the 1947 specifications, although six unlined earth aqueducts were later built on the Bogong High Plains under an austerity programme to complete projects already underway as cheaply as possible.

In the end, Mt Feathertop was untouched by the Kiewa Hydro Scheme except for a line of surveyors' pegs across the steep slopes of Avalanche and Hellfire gullies, extending across to Diamantina Spur showing where the concrete aqueduct and tram line would have been.

A chairlift for Feathertop

The forced sale of the Bungalow after the 1927 ski season and its destruction in the 1939 fires was not the end of plans to build tourist infrastructure on Mt Feathertop. In the 1940s and 50s a few groups dreamed of rebuilding the Bungalow as a club ski lodge or reviving it as a hotel, but in the end nothing happened. However in 1974 an apparently serious proposal to build a chairlift was made.

A company named Mt Smythe Associates* came up with a proposal to build a tourist village on 32 hectares of freehold farmland east of Harrietville and link it to the mountain with a 4 km chairlift parallel to Bungalow Spur. It was to end at an altitude of around 1670 metres. Based on these figures it appears the terminus would have been between the old Feathertop Hut site and Federation Hut. Unlike the freehold tourist village and chairlift base station, the chairlift towers and terminus would have been on Crown land. It would probably have been mainly used by summer tourists in a similar way to Thredbo's highly popular Crackenback / Kosciusko Express chairlift which assists people to climb Mt Kosciusko, but it would certainly have operated in winter as well. It appears the proposal was later modified to a gondola only going as far up Bungalow Spur as Wombat Gap.

* Mt Smythe is a hill on the Great Alpine Road, 12 km south west of Feathertop across a valley known as The Black Hole.

It is unclear how serious Mt Smythe Associates and its chairman Don Handley really were about the chairlift or gondola proposals. They began work on a 19 lot initial subdivision in 1978, but they may have just been floating the idea of a lift or using the suggestion that it might be built as an inducement for people to buy blocks in the subdivision of farmland at the base of the mountain. But opposition to the chairlift, while apparently from only a few people, was fierce. Much of it appears to have come from those who hadn't visited Mt Feathertop or were unaware of its mining history and of the Feathertop Bungalow, as opponents tended to use words such as 'pristine' and 'untouched'. Another tactic was to describe skiing as a sport only for the wealthy, (although it appears that all those who made this wildly inaccurate claim in letters to newspapers came from a few affluent Melbourne suburbs).

It's difficult to tell how widespread opposition to the chairlift really was based on a survey of newspapers of the time. However most of the opponents' arguments appear to have been based more on ideology than protecting the environment of the mountain. In any case, after skirting around the issue for several years, in 1982 the state government firmly stated that it did not support the proposal and it soon faded from media coverage. Nothing more has been heard on the subject since then.

What makes this proposal significant is that it was the first for an integrated mountain village on freehold land, bypassing the expense of bureaucratic delays and complexities when building on Crown land leases. As such, it could be seen as a forerunner of the successful development of Dinner Plain in the mid 1980s.

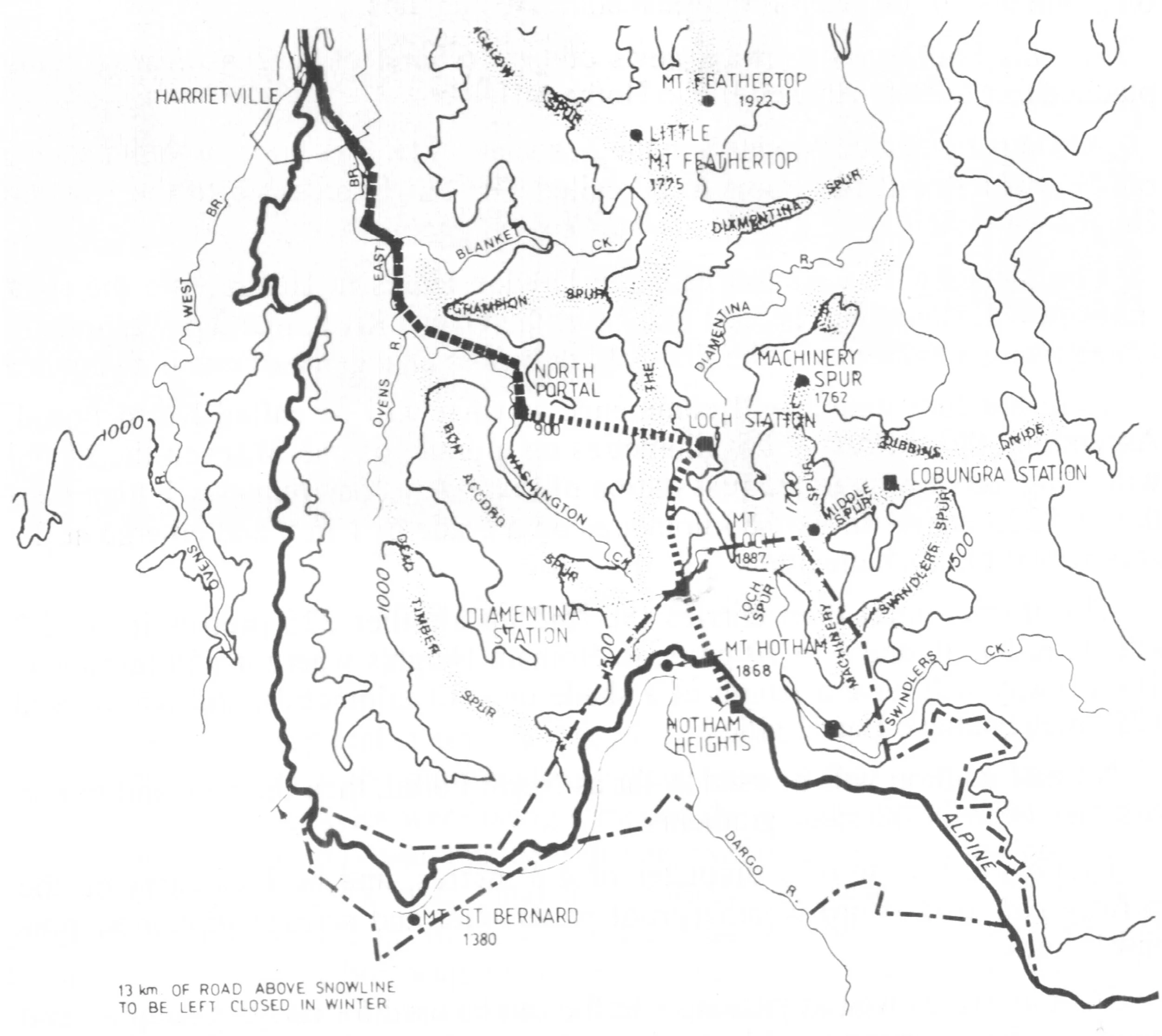

The proposed railway from Harrietville to Hotham with a station on the Razorback. From Wal Larsen. The Ovens Valley Railway. 2nd ed, 1997. p. 160.

Razorback railway station

Even more surprising than an aqueduct and tramway across the east face of Feathertop or a chairlift parallel to Bungalow Spur was an early 1980s plan for a rack railway from Harrietville to Hotham. Maintaining the Great Alpine Road in winter and keeping it clear of snow has always been a huge and expensive task and even today the road is closed by deep snow several times in most winters.

The nearest railhead to Harrietville was at Bright, but while that line was closed in 1983, it was never intended to link the new line with it. Instead the railway was planned to operate as a stand alone route transporting passengers, freight and cars from Harrietville to Hotham Heights during the snow season when the road would be closed between the Mt St Bernard club ski field and Hotham ski resort.

What makes the plan relevant to Mt Feathertop was its planned route. The railway line would have followed an above ground route along the East Branch of the Ovens River and then up the valley of Washington Creek to a tunnel underneath The Razorback with a station roughly half way between High Knob and the Great Alpine Road. Confusingly while the station would be on the Razorback, it was to be called 'Loch', presumably because it would have a view of Mt Loch on the other side of the Diamantina River valley. Then the route was then to swing southwards to an underground terminus in the Hotham Heights area of the resort.

The planned railway was to have grades as steep as 1 in 7, compared to main line railways in Victoria which have a maximum gradient of 1 in 50 or most branch lines, including the Bright line, with 1 in 40. Thus the need for a rack railway where a powered cog on the train would engage a serrated rack between the tracks, eliminating the slipping that would otherwise occur on smooth steel tracks.

If the rack railway had been built and if it included the proposed underground station on the Razorback, it would have greatly improved access to Mt Feathertop. The plan seems to have quietly disappeared after a similar project, the Ski Tube railway from Bullocks Flat to Perisher Valley and Mt Blue Cow in NSW was built and was not as financially successful as its backers had hoped for.

Feathertop Hut. This photo by Jim Tobias appeared in the Weekly Times 22 August 1914

6. Huts

In addition to the large Feathertop Bungalow (see chapters 3 and 4), five other huts have been built on Mt Feathertop.

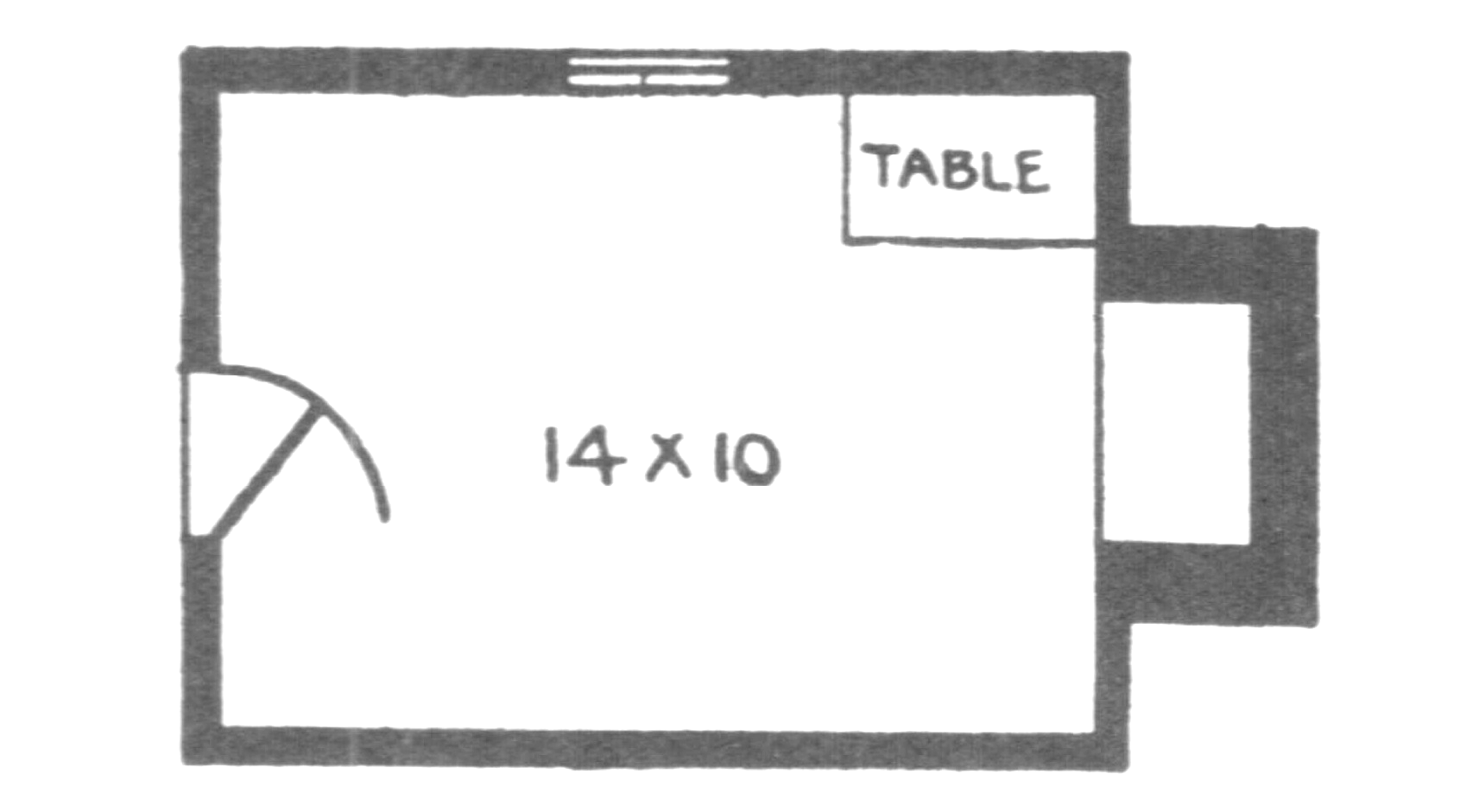

Roy Weston and Cleve Cole's circa 1934 plan of Feathertop Hut.

Feathertop Hut. 1912 - 1980

Located at a height of 1490 metres, Feathertop Hut was erected by a builder named Sloan for the Harrietville Progress Association in 1912, near the top of what would later be named Bungalow Spur. It replaced a 'shelter shed' erected in 1906. Nothing remains of the hut today, but the clearing it stood in, known as The Playgrounds, still makes a pleasant camp site. The hut was corrugated iron, 4.9 x 3.5 metres, pine lined with a pine floor, with six bunks on one side and a fireplace and table on the other side.

Early photos show the chimney next to the door, a fairly standard arrangement for mountain huts in Victoria, but by the 1930s the chimney had moved to the side of the hut with bunks installed where the entrance had been. So it appears that a major renovation had been undertaken at some stage. Feathertop Hut was probably the base for the construction of the nearby Feathertop Bungalow in 1925, so there is a good chance that the hut received a revamp at this time to provide more comfortable accommodation for the builders.

Feathertop Hut, early 1930s. Photo Eric Douglas.

After the Feathertop Bungalow was built, the hut was often used as basic overflow accommodation when the much larger guesthouse was full. After the loss of the Bungalow and Razorback Hut in the 1939 fires, Feathertop Hut was the only building left on the mountain. In 1944 overcrowding led to a 'half loft' being constructed above the ceiling joists using lining boards. As many as five people could sleep in this loft.

With the end of the war in Europe, wartime austerity eased a little and the Harrietville Progress Association commissioned Eric Gravbrot Johnson to renovate the hut, which he did in early June 1945. The bunks and table were replaced, the window and attic were repaired and 'hut equipment' that had gone missing was replaced. Some of the money to pay for this came from the Ski Club of Victoria and after the work was completed the hut could comfortably sleep eight people. Johnson occasionally utilised the pack horses he used on his Bon Accord Spur transport service to Hotham to carry supplies to Feathertop Hut, but the Hotham service was the vast majority of his business.

From the mid 1930s the Ski Club of Victoria controversially tried to assert itself as the peak organisation for skiing in the state. As the war came to an end they decided to impose a fee for use of Feathertop Hut and huts on the Bogong High Plains that they did not own. The SCV pledged to spend the proceeds on hut maintenance and it appears the Harrietville Progress Association allowed the SCV to levy 2/6 per person for a weekend or 5 shillings for a week to stay in Feathertop Hut. This demand for payment to use a hut that had always been free seems to have been met with astonishment from the wider skiing community and it may have been ignored by those not involved with the SCV.

Feathertop Hut (1912 - 1980) with an obvious lean in 1979, not long before it collapsed. Photo © David Neale from Gary Duncan's huts website. Used with permission.

Inter club tensions came to a head in 1947 when the Federation of Victorian Ski Clubs was formed and the SCV refused to join or even acknowledge the FOVSC. From the late 1940s the SCV conducted a rather hostile campaign against the other ski clubs, but in 1955 the heavily outnumbered SCV accepted the inevitable and joined dozens of other clubs in the renamed Victorian Ski Association. Mid 20th century ski politics is a separate issue, but it is worth noting that some of the funds SCV members paid to use the hut were spent on keeping it weatherproof and habitable. However the SCV's involvement only lasted a short time and the April 1948 issue of their newsletter stated that 'Feathertop Hut is now under the full control of the Harrietville Progress Association'.

The site of Feathertop Hut in 2005. © David Sisson

As the years passed Feathertop Hut became increasingly run down. It developed a lean and the chimney partly fell down in about 1960. A typical report of the time is Margaret King's from September 1962. 'We climbed up from Harrietville, and reached the Bungalow Spur Hut late afternoon, to find the chimney collapsed and snow filling much of the rear half of the hut. We managed some clearing and repairs, enough to cook a meal and sleep the night.'

Despite its poor condition, Feathertop Hut remained very popular because there was no other shelter on the very appealing mountain. On 17 August 1963 at least 36 people arrived including a group of 20 from the Catholic Walking Club (which soon became the driving force to build Federation Hut as a replacement). Also present were a group of four mountaineers and a dozen hikers from the Victorian Mountain Tramping Club who wisely opted to avoid the crowds by camping 1 km further up the spur on the treeline.

Jeane Gardner, Marjorie Carr and Margaret Pearson at Razorback Hut in December 1932. Photo: Rhoda Gardner

As the hut deteriorated it became impossible to even close the door properly and it was obvious that the hut was not fulfilling its purpose as a refuge and that it would not remain upright for much longer.

Plans for a replacement hut were first floated in 1954 and in February 1968 the Shire of Bright applied for funds from the Tourist Development Authority to stabilise and renovate the old hut. At the time the Federation of Victorian Walking Clubs had been pondering the construction of a new hut on the site for many years and this grant application may have been an indirect push from the shire to encourage the Federation to make up its mind if they wished to rebuild or not.

Federation Hut was eventually built 1 km uphill on the treeline in 1969 and interest in maintaining Feathertop Hut seems to have ceased at that time. Against expectations Feathertop Hut remained upright, albeit with a pronounced lean, and it continued to provide rough shelter for visitors to the mountain until it finally collapsed in the winter of 1980. At the time there was three metres of snow on the ground and a metre of snow on the roof, but the two occupants of the hut emerged without injury after it collapsed.

Razorback Hut. 1929 - 1939

Razorback Hut was a small and basic iron shelter on the Razorback ridge at an altitude of 1624 metres, located in a saddle about half way between the Great Alpine Road and the base of Feathertop's summit pyramid. The hut was owned by the Tourist Resorts Committee and was built in 1929 as an emergency shelter by an unidentified government agency. It measured approximately 3 x 4.25 metres and featured a dirt floor, a fireplace, a table and a small window. It appears there was no tank and water had to be obtained hundreds of metres to the north on the west fall of the ridge.

Razorback Hut. Photo Roy Weston, circa 1931.

Before the Second World War, the ski tour between the Feathertop Bungalow and Hotham Heights guesthouses was a fairly popular excursion for experienced skiers and the Razorback was sometimes used as an alternative access route to Hotham, although the route via the hotel on Mt St Bernard and the direct ascent via Bon Accord Spur were both more popular. It seems that skiers only regarded Razorback Hut as an emergency shelter as there are no surviving reports of people planning to spend the night there in winter or basing themselves at the hut to ski the steep slopes of the Razorback.

The very simple layout of Razorback Hut. Drawn by Roy Weston and Cleve Cole c.1934.

However the hut was also used by mountain cattlemen, as it was on the Lawler's droving route along the Razorback between their property on Snowy Creek and their grazing lease on Hotham. They built a horse yard just downhill of the hut.

Along with most of the surrounding area, Razorback Hut was burnt in the Black Friday fires of January 1939. The Second World War began seven months later resulting in shortages of money, labour and building materials, so the hut was not replaced.

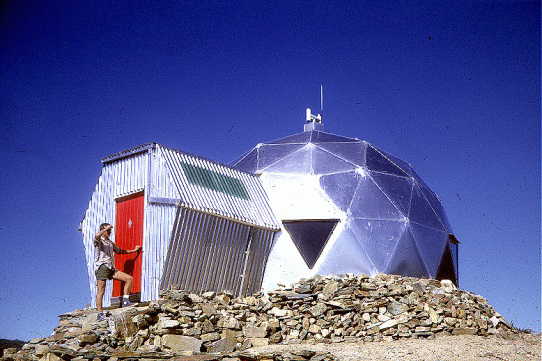

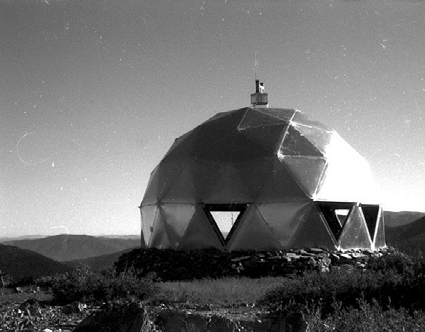

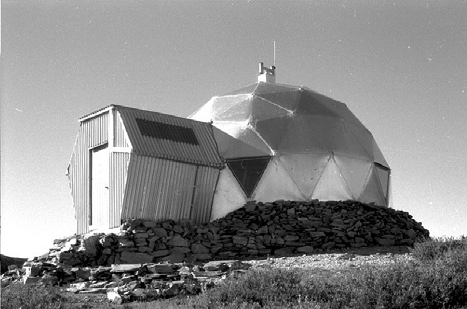

M.U.M.C. Hut in 2006. Photo © David Sisson.

MUMC Hut

Mt Feathertop Memorial Hut 1966 -

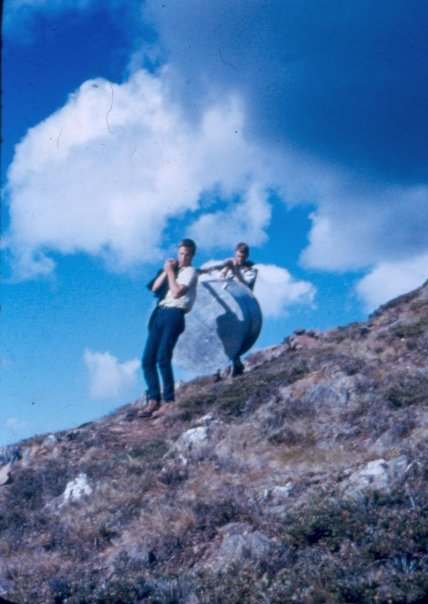

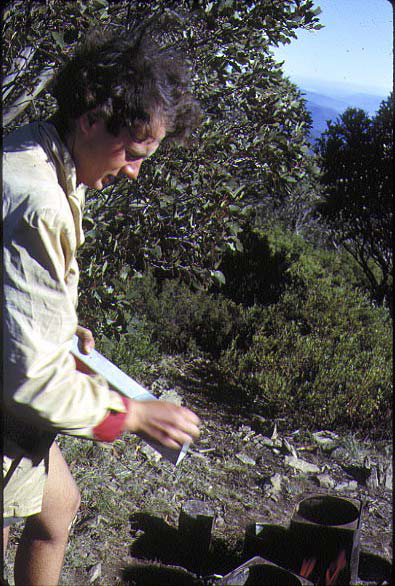

Undertaking a survey. At The Cross looking towards the proposed building site. Queens Birthday weekend 1965. Photo © Peter Kneen. Used with permission.

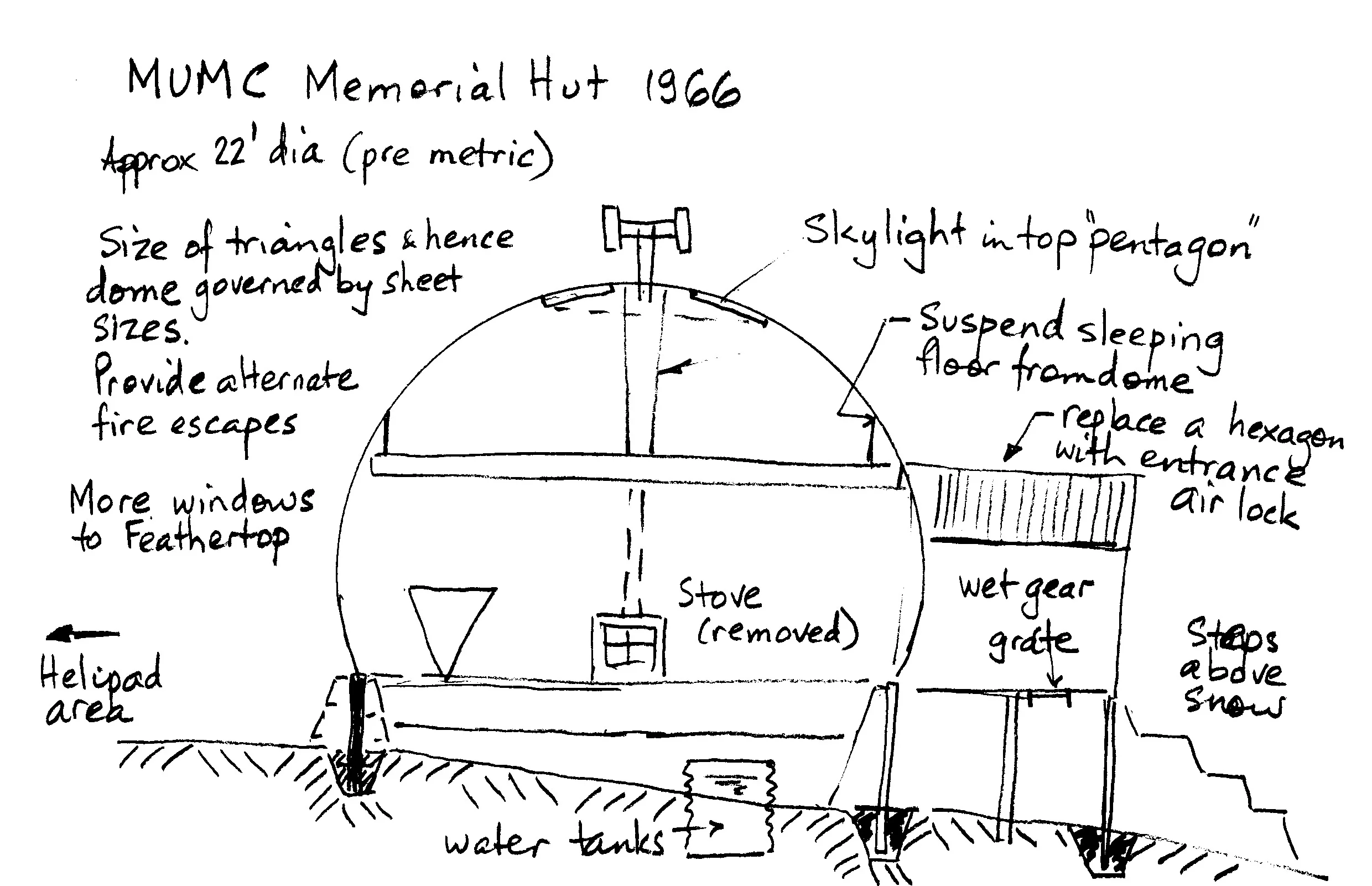

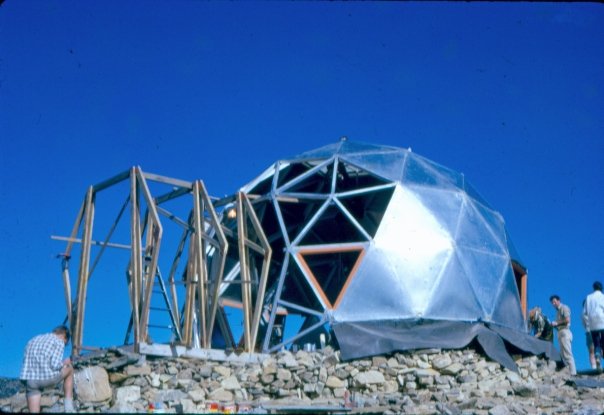

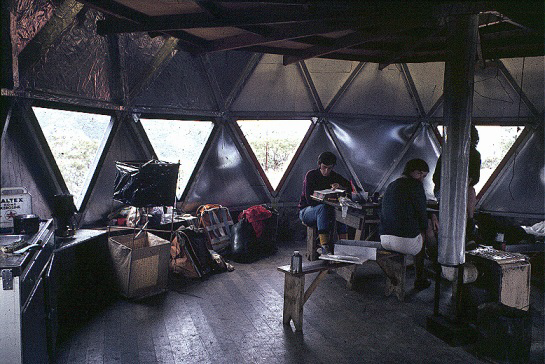

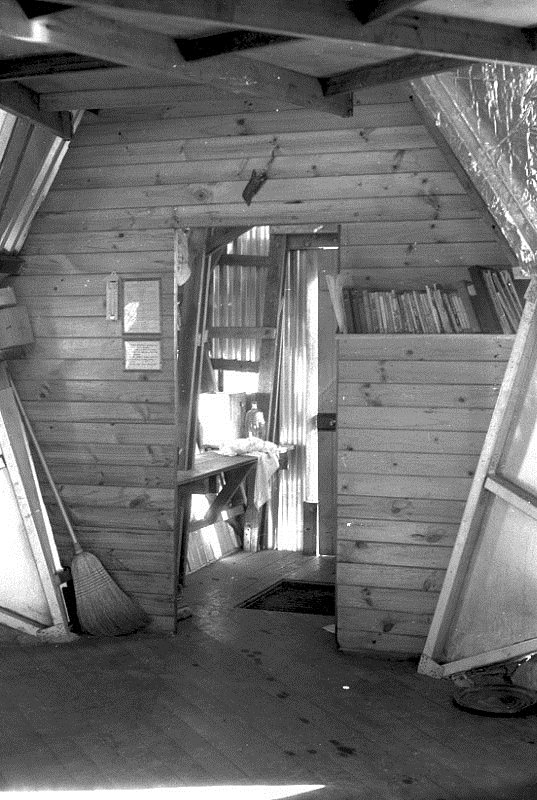

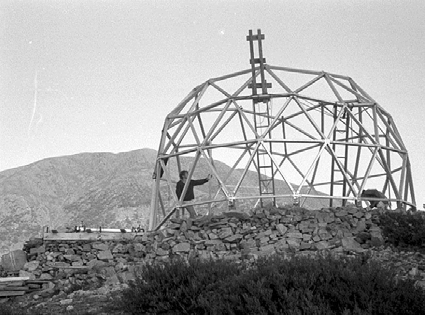

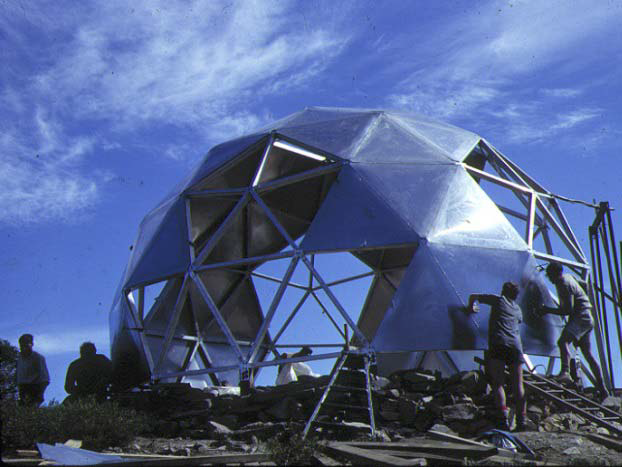

In the summer of 1965 - 1966 the Melbourne University Mountaineering Club built the distinctive MUMC Hut at the top of North West Spur at an altitude of 1610 metres. Along with Cleve Cole Memorial Hut on Mt Bogong, it is one of the biggest huts in the mountains. (Frys Hut and Moscow Villa are larger, but they are in mountain valleys.) It has a sleeping platform suspended above the main living area with a locked storage cellar below it.

Planning, designing and building the hut to lock up stage in less than a year was a phenomenal achievement, especially when it is remembered that this was a mainly undergraduate club with a very young membership; most members were in their late teens or early twenties.

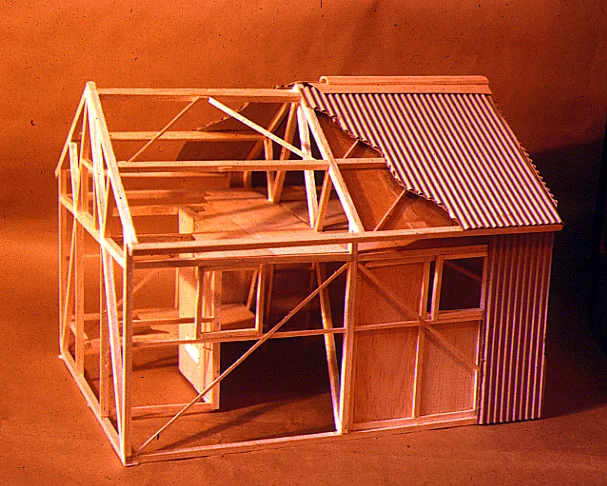

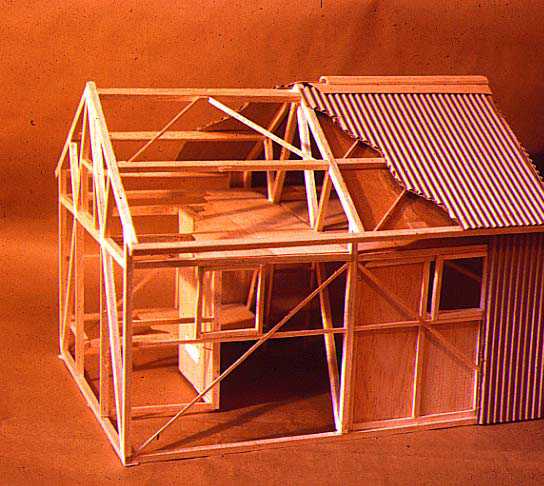

A model of one of Peter Kneen's proposals for MUMC Hut. It was later was adapted by Paul Kennedy as the basis for the first Federation Hut elsewhere on Feathertop © P. Kneen

In the 1960s, the MUMC was more than a standard student hiking club and it was more active and productive than other Victorian outdoor clubs. In addition to its outdoor activities, it published a Guide to the Victorian Alps for hikers and two editions of Equipment for Mountaineering. Club members also actively participated in activities such rock climbing and mountaineering. Two members, John Young and John Vidulich had died climbing on Mt Cook in New Zealand in 1955. Another member John Hodgson died on Mt Sealy in 1957 and in early 1965 Russell Judge and Doug Hatt were killed in an avalanche on Mt Cook.

With five deaths in New Zealand's Southern Alps, the club decided they needed a local base where members could learn mountaineering skills. Mt Feathertop was an obvious location.

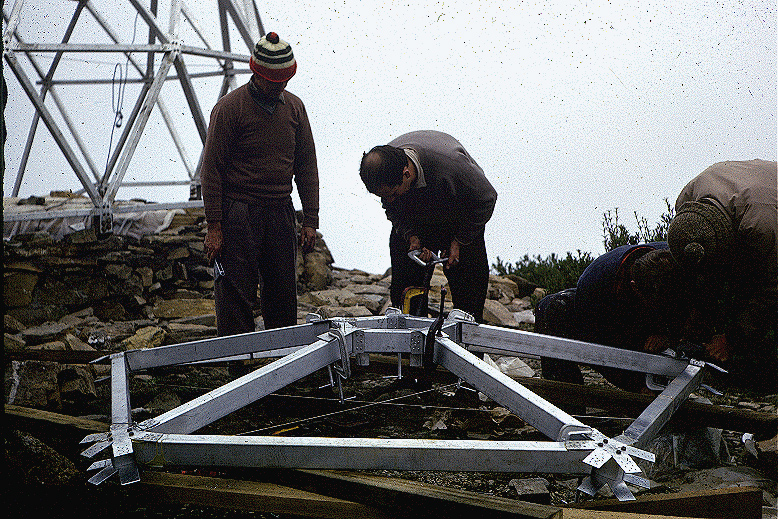

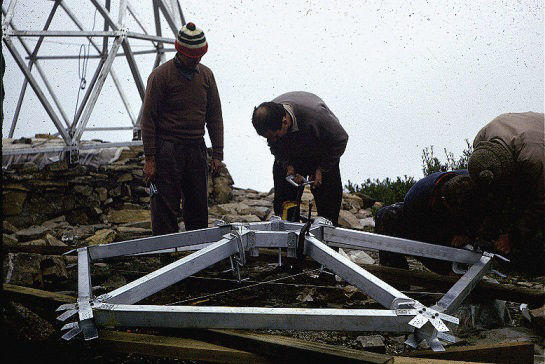

Building the hut

For over a decade there had been protracted discussions about renovating or replacing the dilapidated Feathertop Hut on Bungalow Spur, but at the time it looked like no decision would ever be made. It is possible that the need for a solid hut on Feathertop influenced the MUMC to choose a location elsewhere on the mountain as their base. After 15 years of discussion Federation Hut was eventually built in 1969 and Feathertop Hut was left to finally collapse in 1980.

Unlike the drawn out Feathertop Hut replacement saga, the MUMC moved fast. In April 1965, three months after the deaths on Mt Cook, the decision to build was announced and Dave Allen, John Retchford and Peter Kneen undertook a survey of possible sites for a memorial hut before the 1965 winter. Peter Kneen states that the location at the top of North West Spur was chosen over Bungalow Spur as 'it was off the tourist track a bit. We were concerned partly with vandalism... and felt that people that put some extra effort into getting to the final site would appreciate it more.'

A second proposed design for MUMC Hut, © Peter Kneen. Used with permission.

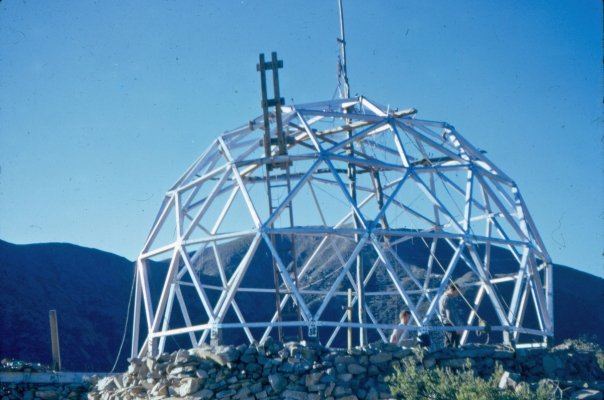

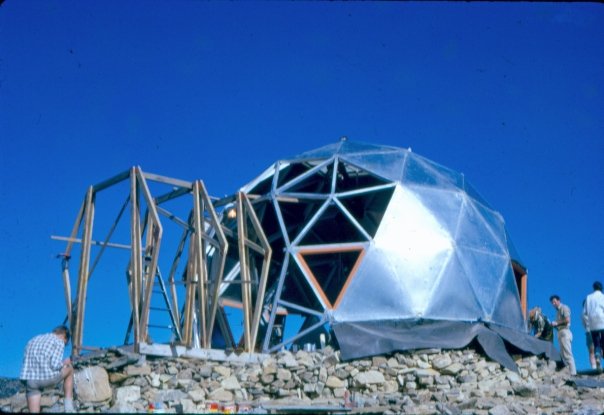

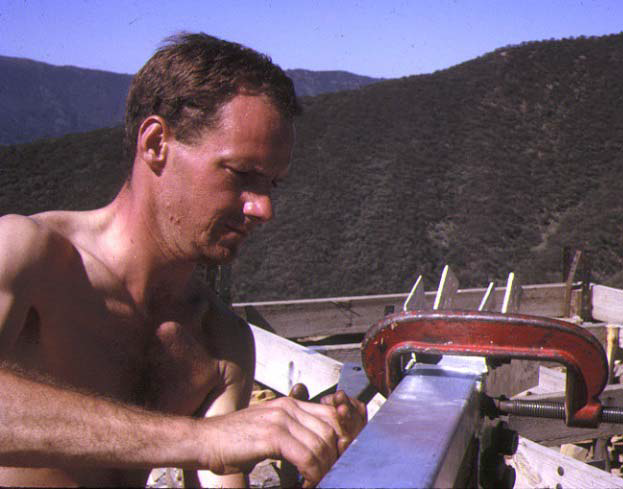

Peter Kneen was a final year civil engineering student and came up with three designs for the hut. One was a fairly conventional looking tin hut and his plans were later adapted to become Federation Hut. The second was a square shaped design with low stone walls and four distinct gables dropping to curved valleys. Kneen says that the stone walls were influenced by Cleve Cole Hut on Mt Bogong. The third design, dubbed 'the igloo', was the most radical. This was 20 years before dome tents became common and the geodesic dome was unlike anything seen before in the high country.

The design had the advantage of maximizing usable interior space and, being made of short sections of aluminium framing and covered with panels, it was possible to carry in all the building materials.

Over the winter of 1965 the hut design was finalised, a permissive occupancy lease for the chosen location was obtained from the Mt Hotham Committee of Management, materials were sourced and the club was ready to commence building as soon as student exams were over.

MUMC Hut floorplan. From Graeme Butler & Associates. Victorian alpine huts heritage survey, 1996. p 204. Used with permission.

Peter Kneen's sketched cross section gives more of a feel for the design of MUMC Hut than the Butler floor plan.

The upstairs sleeping area suspended above the main living area. © David Sisson

Against an estimated cost of £950 to build the hut, the club was able to contribute £200 from its reserves and an energetic fund raising campaign was undertaken to obtain the rest. Raffles, parties and auctions all contributed to the cause. The club also approached former members and other interested people, as well as gaining publicity for the project in The Age newspaper. It appears that donations from outside the club comprised the bulk of the money raised. To allow work to begin before all the funds had been raised, the University of Melbourne lent the club £300.

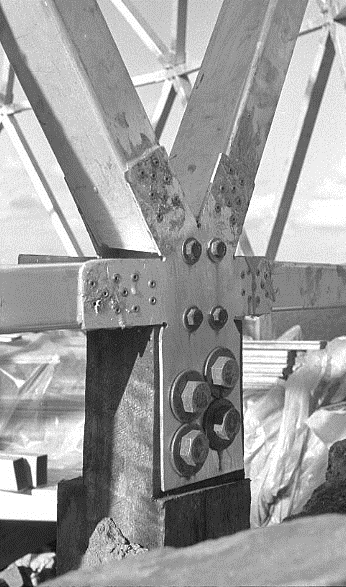

Before construction could start, building material had to be bought, components such as the aluminium frame had to be prefabricated and the panels that were to clad it had to be cut to size. This was a major task on its own, for example after components of the frame had been made, 14,000 holes had to be drilled in them ready for the pop rivets that would be inserted when the hut was erected.

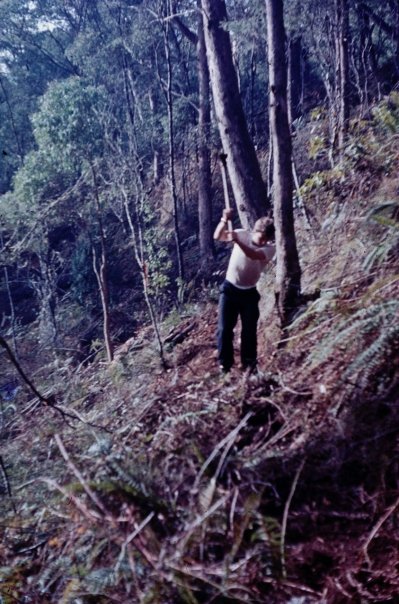

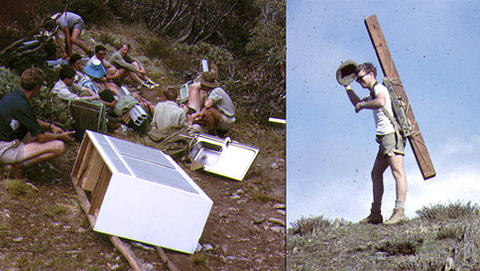

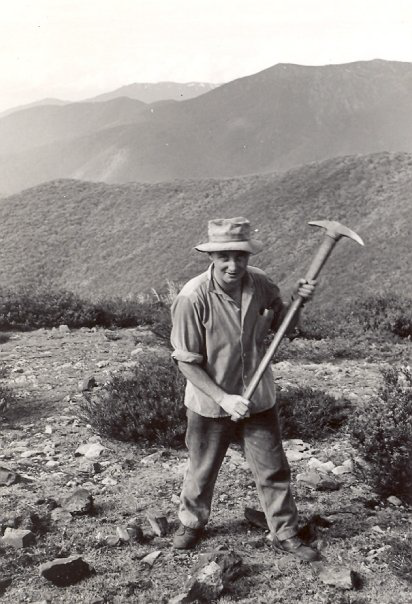

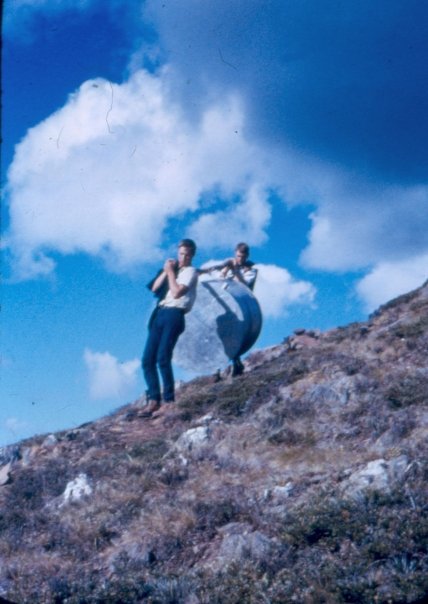

Transport was a huge task. Five tons of building material, half a ton of tools and two tons of food had to be driven from Melbourne to the road-head at the end of the newly extended Stony Creek Track on the North Razorback in Land Rovers. ('A friendly bulldozer driver extended the logging road... by one km.') It then had to be transported to the site. To save money, it was decided not to use pack horses or helicopters, everything was to be carried in by club members.

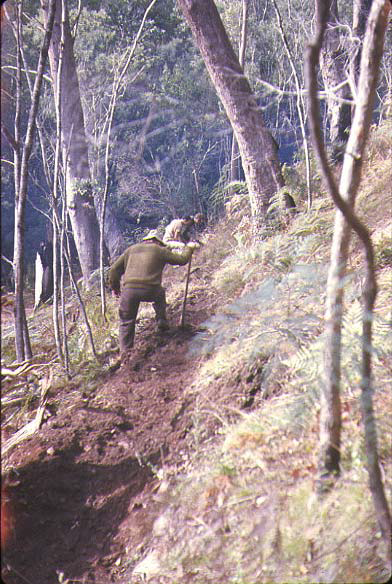

Despite a few forays up the then untracked North West Spur, the main access route decided on was the Lawler family's old droving route that bypassed the summit to the west. Grazing licences on Feathertop had been withdrawn in 1958 and the old cattlepad had become overgrown. So before work began the route was cleared and benched into the hillside to provide a good track for the porters.

In addition to loads of tools, cement and food that could mostly be carried in conventional packs there was a lot of heavy or awkward material that had to be shifted including two 682 litre water tanks, a generator, a rock drill, 32 kg redgum foundation posts, floor bearers, a wood burning stove, large aluminium panels and a kitchen sink complete with a cupboard frame for it to sit in.

A start had been made on building a 'winter access route' up the North West Spur, but the track was not completed until well after the hut was finished. While material was carried up it on a few occasions, it took more than twice as long as walking in from the North Razorback road. After Tom Kneen, the equipment officer for the hut construction project (and cousin of the hut designer) died in a Feathertop cornice collapse in 1985, the North West Spur track was named in his memory.

Construction began on 5 December 1965. The first task was to excavate the cellar and install the foundations and redgum stumps. This was followed by excavating 25 tons of stone (assisted by a petrol powered rock drill) and moving it to build the steps and the wall that surrounds the hut. The frame was then assembled and clad with pre-cut triangular panels. As silicon sealant was not yet available the panels were sealed with 27 kg of Araldite epoxy resin.

The volunteer builders stayed at a sheltered base camp to the south east of the hut site in the headwaters of Stony Creek. A kitchen was established to feed them and they were charged 10/- to 15/- for food for a weekend. Major construction work was finished by March 1966 and 'finishing details' such as completing the interior fit-out were completed within a year. Against an initial estimate of £950 ($1900) the total cost of the complete hut was $2480. (Australian currency was metricated and changed from pounds to dollars in February 1966.)

There were over 200 volunteers involved with the project. Those in Melbourne worked on fund raising, organising transport, sourcing supplies and prefabricating them as much as was practical. Those on Feathertop were kept busy with a variety of tasks. There were track builders constructing the new track that bypassed the summit, porters delivering supplies to the construction site from the recently extended roadhead on the North Razorback, labourers assembling the hut under close supervision. carriers bringing water from a nearby creek up to the construction site for making cement, and many other jobs. As was usual at the time, the men mostly did the construction work while women were in charge of catering. It's worth recording the names of the principal protagonists:

Hut Sub-Committee Convener Nick White Secretary, Jenny McMahon

Treasurer, Richard Schmidt. Design Officer, Peter Kneen

Catering & Fund Raising, Nina Rulevich Equipment, Tom Kneen Draftsmen, Tony Kerr and Cath Milvain Transport, Ron Jellef

Purchasing Officer, Lindsay Hackett. Packaging Officer, Bob Dewar

Reporter & Publicity, Margot Osborne

Track Clearing & Club President Phil Waring

Photo galleries of the construction of MUMC Hut provided by Peter Kneen

![This is a sketch of the original proposal for a hut. It was based on the approximate size of the hut on the Bungalow Spur. [Feathertop Hut built in 1912.] However the internal framing was very different which would have resisted the tendency](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54b4bb3ee4b07950683ef3ba/1454098700683-RI15LJ4ITBRBJ4EN8XSS/7.png)

MUMC Hut interior showing the ladder leading to the upper floor. © David Sisson

Little MUMC Hut (the toilet). An equally radical statement as the main hut. Designed and built by Robert Vincent, burnt in the 2003 fires.

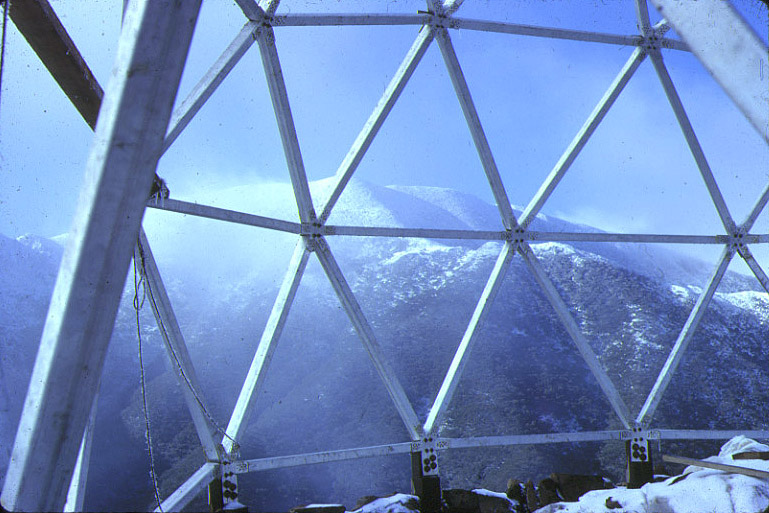

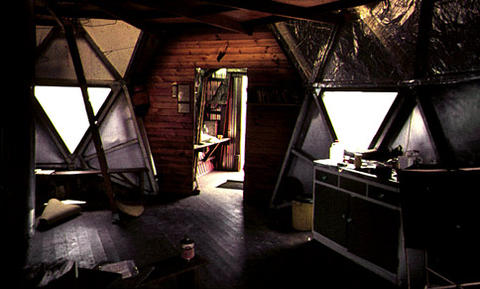

Hut description

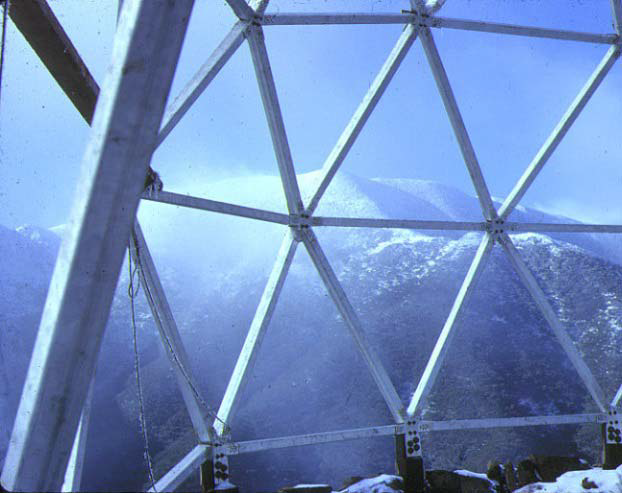

The hut is circular, 6.4 metres in diameter at floor level, with a wooden floor in the spacious living area. The aluminium dome sits on a stone plinth which provides the lower section of the hut wall. A ladder leads to an attic sleeping platform suspended above the main room that can accommodate about 15 people. The hut has seven triangular windows letting light onto the living area with more windows facing towards the summit than in other directions. Furniture is fairly sparse, there are some seats against the walls and a large table with a pair of wooden benches.

The 2.3 x 3 metre entrance porch is clad in aluminium panels and has racks for storage of packs. It also provides a useful airlock between the interior and the weather outside. A locked grill in the floor of the entrance provides access to a storage cellar. Water is harvested from the roof of the entry porch and stored in tanks located in the cellar. There is a small sink against the living room wall and water is raised from the tanks using a hand pump.

There is little doubt that the hut was designed to make a statement. A 1996 heritage survey of mountain huts described it as 'reflecting the avant-garde architectural experimentation of the post-war era by the use of the geodesic dome and aluminium cladding'.

What is important is that the 'experimentation' also worked remarkably well in the hut's principal function as a mountain refuge. For over 50 years the hut has withstood often appalling weather while providing a large and comfortable living area and separate sleeping area. One of the minor details is that the door faces roughly north east so it catches the morning sun, but it also directly aligns with the summit of the Fainters, a reminder when exiting the hut that Feathertop is not the only high and steep mountain in the area.

One drawback for hut residents, (at least when compared to the cosy rebuilt Federation Hut nearby), is that it is a fairly cold hut, especially since the wood burning stove was removed. Insulation of polystyrene foam cut to fit inside the panels of the hut frame and covered by aluminium foil was originally installed, but it often became detached. Today most of it appears to have been removed.

Ventilation isn't usually a problem with traditional mountain huts built from wooden slabs, logs or corrugated iron, but the fairly well sealed hut has suffered problems with condensation leading to drips on people sleeping on the top level. Over the years leaks developed where the panels joined and these were attended to with varying speed according to the level of involvement from the changing committee of the student club.

So perversely, the hut sometimes leaks when it is raining and suffers from condensation drips when it isn't raining. Along with the peeling insulation, these were the major flaws of an otherwise well designed hut. But structurally the hut has been a great success and it has withstood everything that fifty years of wild mountain weather has thrown at it.

When the hut was built the silver aluminium covering was left unpainted, but complaints that it reflected the sun soon caused it to be painted a drab green, followed by a repaint in 1977.

The hut survived the 2003 wildfires, albeit with a temporary pink colour from the phos-chek fire retardant that a helicopter pilot thoughtfully dumped on it. However Little MUMC Hut (the toilet) was burnt. It was rebuilt in 2007.

While the hut is best known in club circles as the venue for an annual midnight ascent of the mountain, it is still used by the MUMC for its initial purpose of mountaineering training. Over the years other groups have used it as a base for training courses including the Australian Section of the New Zealand Alpine Club in the late 1970s. MUMC Hut remains a spacious and comfortable hut although it only receives a fraction of the visitors that nearby Federation Hut gets.

The old Federation Hut with its original cladding. © Tony Marsh. Used with permission.

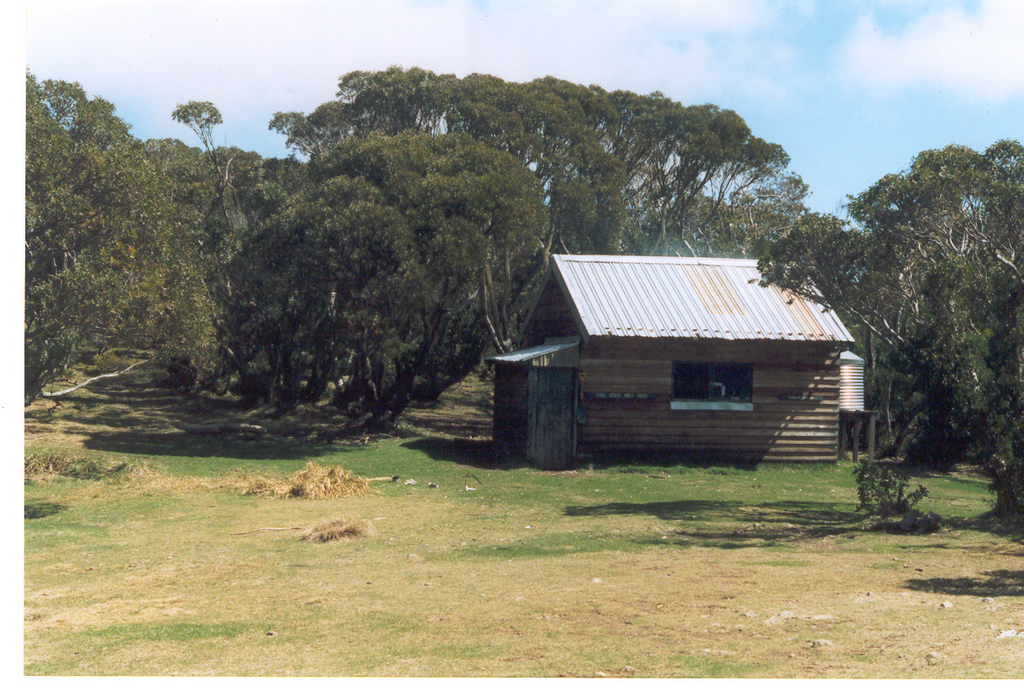

Old Federation Hut. 1969 - 2003

In the summer of 1969 the Federation of Victorian Walking Clubs built Federation Hut at 1690 metres on the tree line at the top of Bungalow Spur. The location was already a popular campsite in both summer and winter as it was on ski runs that had been cleared of trees before the Second World War in the days of the Feathertop Bungalow guesthouse. The area provided the highest sheltered campsites on the most popular route up the mountain.

Plan of the original Federation Hut. From: Victorian alpine huts heritage survey, 1996. p 102

By the mid 1950s, it appeared that the old Feathertop Hut, just uphill from the site of the Bungalow, was approaching the end of its life and the Federation of Victorian Walking Clubs began to consider renovating it or building a replacement. In the 1950s this was just an idea tossed around by Federation committees and constituent clubs, but by the 1960s, serious proposals began to emerge. However being a federation, there were a multitude of views held by members of those committees and by the individual clubs, so things moved rather slowly and it appeared that the project would never progress beyond endless discussion.

This paralysis was broken by the example of MUMC Hut on the North West Spur of Feathertop, which was conceived, designed, authorised and built in just 11 months.

Two plans for a new hut on the old Feathertop Hut site were drawn up by Paul Kennedy, one was a similar design to the original hut while another was an A-frame. This was a popular style of snow architecture at the time and A-frame lodges still survive at three Victorian ski resorts as well as Diamantina Hut on the Great Alpine Road and the remote Vallejo Gantner Hut built on Mt Howitt in 1970.

It seems the main push to build a new hut was led by members of the Catholic Walking Club notably Paul Kennedy and Tom Buykx, while the Melbourne Walking Club and the Melbourne Bushwalkers opposed the project, although at the time both these clubs had their own private lodges elsewhere in the mountains. (The MWC owned the last surviving ski lodge at Donna Buang while the 'Bushies' owned Wilkinson Lodge on the Bogong High Plains.)

Building old Federation Hut. Photo Tom Buykx