Timber trams

This page is being developed. Further articles and photos will be added in the future.

Timber tramways were a major feature of Australian mountains in the first half of the 20th century. Trees were felled with a broad axe and crosscut saw and moved to nearby mills by winch, horse or tramway. The mills were typically located deep in the forests and the sawn timber was usually moved to the nearest railhead by a steam hauled train. The infrastructure associated with these tramways is astonishing, long tunnels, towering bridges and extensive earthworks, all built by cash strapped mill owners in the knowledge that they would be abandoned after 20 years when the nearby timber was cut out.

After the Second World War the mills were moved out of the forest to nearby towns with the logs moved by road. Today the forests harvested a century ago have regrown, but it is still common to find relics of this earlier era of mills deep in the forest and the tramways that served them.

Timber trams operated throughout Australia, there were was a network of firewood tramways heading out of Kalgoorlie in the arid Western Australian goldfields. But they were especially characteristic of the tall montane and sub alpine forests of south eastern Australia.

Along with miners, mountain cattlemen and later hydro electric developments, the timber industry was one of the main reasons the mountains were opened up and became accessible. The sawmills, tramlines and the people who worked on them represent a lost way of life. People no longer live and work deep in towering forests, our ancestors were a lot tougher than we are.

Dozens of books have been written on the timber trams and the sawmills they served. The Light Railway Research Society of Australia actively researches timber tramlines and is a prolific publisher on the subject.

Contents

- Walking the timber tram lines. A. D. Budge.

- A ride on the bush line. Hugh Richards.

These articles are over 50 years old, but deserve to be read again. However some may still be copyright. If there are any objections to an article being republished here, please send an email and I will remove it immediately. David Sisson. sisson dot dave at yahoo dot com dot au

Walking the timber tram lines

By A. D. Budge. This article evokes the atmosphere of the timber trams and the communities they served better than any article I have read.

Alan Budge (19xx - 199x) was a keen hiker, a prolific writer and editor of The Melbourne Waker, a widely circulated annual publication of the Melbourne Walking Club. This article wonderfully describes Budge's experiences in the forests east of Melbourne before the Second World War.

A completely new generation of walkers has grown up since timber was milled deep in the forests, sawn to commercial sizes on the spot, and brought out many miles along winding tram lines to the nearest railway. They were the days before chain saws, crawler tractors, bulldozers and powerful prime movers hauling swaying timber jinkers piled high with logs over remote mountain roads.

In those days, the timber men lived at the mill sites, with the opportunity of visiting a town on Saturday afternoon and Sunday only. They climbed the tall mountain ash, cut off the top branches, and then the bole was felled with axe and crosscut saw. If the terrain was suitable, the logs were hauled by cable and winches along "snig" tracks, which were furrows in the ground, guiding the logs to the saw mill. Sometimes, if snig tracks could not be used, the logs were carried on a system of cables, called a "high lead" across gullies and over tree tops. Often, spur tram lines radiated from the mill to bring in the logs. These tracks were roughly laid with sawn timber rails and sleepers, on which the broad flanged steel-wheeled timber trolleys were hauled by work-horses, big plodding animals which patiently pulled their heavy loads in all kinds of weather. However, if the gradient was too steep for horses (and often it was), the trolleys were lowered to lesser levels or hauled to grater heights by cables. After milling, the timber was loaded onto sizeable trains made up of timber trolleys, pulled by a steam locomotive. No standard model of locomotive existed, and the variations were many. They had one thing in common: they all traveled with a great deal of fuss and noise. Sometimes horses were used for this final haul if the going was fairly level and the distance was not too great. The tracks in later years were often of steel, but timber rails, or a combination of timber and steel, were used.

There were many railway towns that were outlets for the timber traffic. Warburton, Millgrove, Wesburn, Yarra Junction, Launching Place, Woori Yalock, Healesville and Gembrook are obvious ones, but others included Noojee, Neerim South, and further afield, Moe. At one time a tram line from the Spion Kop area crossed the Princes Highway and finished at Longwarry railway station. Tram lines penetrated the forests in many places. The snaked their way up the Tanjil and Tyers Rivers to the lower slopes of the Baw Baws; in 1940 a line was operating in Upper Lerderderg, below Bullarto, and they climbed the slopes of Mt Samaria in the Broken River area.

The Powelltown passenger train.

This network of tram lines presented many opportunities for fascinating walking tours of week-end, long week-end, or even Easter duration. A way into such country was to travel to Yarra Junction on the Saturday morning train. This was met by the Victorian Hardwood Company's train, which traveled to Powelltown. The train consisted of a locomotive, a rake of empty timber trolleys, and a passenger coach at the rear. The word "coach" is a brave one; obviously it was a home made job, built of timber, seemingly without springs of any kind. Seating consisted of two lines of wooden straight-backed benches along each side and one scrambled in amongst mail and freight, found a place to dump the pack and fought a way to a seat - if there was one. There were passengers other than walkers, but invariably they were mill workers, their women - folk and their children. With a bone-shaking, teeth-rattling jerk, the whole contrivance started. and soon the conductor-cum-guard appeared in order to collect the fares. This official was definitely a bush character, who never ceased to wonder at the antics of "youse city blokes" who came up to came up to the hills to wander around during the week-ends. Many times he told us in forthright terms just what he thought of us, but, bless him, he had a heart of gold for all that, and one feels enriched for having known him. One must admit that traveling by car over this route to-day is a poor substitute for those past journeys. And all it cost was a modest shilling.

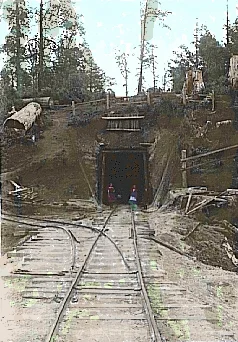

Once on the Powelltown train, one had a world of walking on hand. One could leave the train at Black Sands and follow tracks and fire-breaks to Britannia and Mississippi Creeks, or to Mt. Bride and Warburton. Or, on alighting at Gilderoy or Three Bridges, there was the country down south to Gembrook to explore. From Powelltown there was a host of routes to follow. The main tram line could be walked (no passengers on this section) up to the head of the Little Yarra River, where there was a tunnel under the Yarra - La Trobe Divide. It was fun to grope through this tunnel rather than climb over the top, but one always took the precaution of making enquiries as to the possibility of a timber train being in the vicinity. There was no room for both walkers and a rake of trucks in that tunnel at the same time!

From the tunnel there were lines to Upper Goodwood, to Knott's Mill, to the case mill near the junction of the Ada and Little Rivers (surely one of the most beautiful of all stream junctions, but it was destroyed in the 1939 fires), to the steep 1400-feet rise known as the High Lead, then down into the Ada Valley and out to Starling Gap, with a hurried rush to Warburton to catch the Sunday evening train. If there was time there were devious ways through to Noojee. One cannot forget the long winding tram line from Big Pat's Creek township out to Richard's Mill on Starvation Creek, with all those magnificent fern gullies, which were headed every mile or so. The twenty mile walk into Warburton from the mill did not seem so far under the spell of such beauty.

However walking through forest country was not the only pleasure in those days. One can do that now along the many jeep tracks and fire lines of to-day. There were people to meet, because hundreds of people lived in these forests. In the main, they were friendly people, real bush people and not just town folk living in the bush. All walkers who knew those days will remember occasions when they arrived in poring rain at a mill and were given permission to sleep in a vacant hut or in the mill building itself. We listened to the many stories, stories full of interest, told by the older timber men about the milling days of the early years of this century. Then there were certain walkers who always seemed to know where a cup of morning or afternoon tea could be obtained (often gratis) at a mill boarding house.

This was the happy side of walking in these milling areas, but life was not always easy for bush people. One remembers the sad-eyed women living in rough unpainted sawn weatherboard shacks at a mill far removed from the comforts of life, and their sole link with the outside world an insecure perch on a load of timber carried by a train rattling its way through the bush. Or the men who, in order to visit their folk in Warburton during the week-end, although able to hitch a ride on a timber train on Saturday, would have to walk ten, fifteen or twenty miles on the Sunday to ensure they would be at their jobs at 7.30 a.m. on Monday morning. Or there were the long periods of enforced, unpaid idleness they had to endure during winter, when prolonged rain, or snow on the ground, made work impossible.

The timber milling of the tram lines era has gone for ever, and, in spite of the many pleasures it gave to walkers, one cannot deplore its passing. The death rate among timber workers during the 1939 fires finally proved the futility of allowing large communities to live in the forests. Not only was there an impossible task of getting people out along those winding tram lines in a fire menaced area, but there was the danger of fires originating from such settlements. The development of heavy mechanical equipment during the last thirty years has abolished the necessity for any workers, other than tree fellers and transport men, to be in the forest. For the security of people and the forest in general, this is all to the good, but one cannot help having some regrets.

By A. D. Budge. From The Melbourne Walker. Volume 39, 1968. pp. 75 - 78.

A Shay locomotive on a trestle bridge near The Bump tunnel.

A ride on the bush line in 1927

Hugh Richards.

Powelltown swelters under a blazing summer sun. The gums on the slopes of the surrounding ranges are masses of bright, dry, green, streaked with the slim, straight whitenesses of the trunks. The big tin roof of the sawmill shimmers with reflected heat. Black smoke ascends sluggishly from the tall chimney stack. Dust- hot dust-lifts from your feet as you walk.

And eternally the drone of the sawmill rises and falls, monotonous and persistent as the heat.

Shunting trucks of timber from the sawmill platform, the squat little engine with the enormous stack whistles with the assurance of an A2. You disturb the swarm of flies enveloping you and study your watch. The young foreman beside you answers your thoughts.

"She'll be leaving inside half an hour," he says. "I suppose there'll be ten logs for her to bring in. About nine miles to ten miles out she goes. Climbs all the way there."

"Will it be any cooler?" You jerk a thumb towards the ranges, flick some of the flies irritably from your face and wave them on the foreman.

The foreman waves them back to you. "When you get in amongst the trees and over the creeks, it will. That is," he grins, "if you don't run into a bushfire.''

You moisten your lips and survey the sprawling ranges anxiously. Not the slightest sign of fire, not even a solitary whisp of blue smoke anywhere. All the same, this heat . . .

"We make three trips for logs every day,"continues the foreman casually.

"That gives us, say, 30 logs to slice and stack daily- 30,000 super feet of timber. Our tram line takes it to Yarra Junction, and from there its railed to Melbourne."

The shade of the mill is not much cooler than the glare of the sun, but it looks cooler. Under the hot tin shelter, you watch the flashing, revolving, saws slicing through the slabs of hardwood, and listen to the drone of their unchanging dirge.

All mountain ash

"Hard wood and good wood," the foreman shouts. "Mountain ash we handle here. It's used for interior building structures, motor bodies and the like. When it is seasoned and polished, they call it Australian Oak. It makes fine furniture. We season about 10 to 15 per cent.

Machinery does most of the lifting and handling in the Powelltown sawmill. Lanky iron arms roll the logs into proper position under the big saws. Mechanical conveyors trundle the flitches under the smaller saws, and slides the scantlings to the stackers. Sawdust travels in thick masses along ascending runways to the furnaces. Underneath the false flooring huge machinery throbs and pounds.

At the roaring furnaces by the three boilers, a stoker juggles huge pieces of firewood. Even the merciless rays of the sun are preferable to the overpowering burst of heat from the furnaces. The very air is on fire.

And, under the sun-drenched tin roof, the saws drone and drone . . .

But the log train is ready for its climb into the heart of the hills. The engine is drawn up at the head of the long row of low, open trolleys-each merely a bare framework on four sturdy wheels. You perch yourself on the front of the leading trolley, shift your feet clear of the uncovered wheels and wave farewell to the foreman. Immediately in front of you is the stolid rear of the engine, topped by an immense stack of firewood.

The whistle shrieks. The train shakes itself into movement. The wheels beneath you bump forward. Couplings clank the whole length of the train. Grinding and jolting on the light, narrow-gauge rails, the train climbs and winds out of the yards, whistles as it labours across Powelltown's main street, and determinedly sets its snorting nose at the steep ranges.

Fainter and fainter sounds the omnipresent whining drone of the sawmill . . . fainter and fainter . . .

Rusty rail, wooden sleepers and rough tracks slither under the wheels of the engine and slide beneath your feet. Pungent smoke whisps around the blackened roof of the cab. It is a stiff climb and a hard pull for the little locomotive.

On either hand, the steep slopes of the ranges sweep to the blue, unclouded sky. Thousands of bare tree trunks stand like soldiers on parade. Foliage has not yet freshened all the ravages of the bushfires which, a year or so ago, ringed Powelltown in a circle of raging flames. But a young generation of green saplings is springing up.

Onward and upward

Twisting across a high trestle bridge, the train turns to the left. A hundred feet or so below in the valley lie ugly looking rocks. The line disappears between high narrow banks, which almost brush the sides of the swaying engine.

Onward and upward . . . Clanking of piston rods . . . Grinding and bumping of wheels.

A bronzed giant in a flannel shirt, belted trousers and two days growth of whiskers backs off the engine and swings himself on to the front of the trolley beside you.

"Slow enough, isn't it?" he says. "We'll show you some speed coming back, though. You see, we leave these trolleys with the other engine at the top, and pick up the logs which are waiting for us on the trolleys we left there the other day. Follow me?"

"Now, its a run downhill all the way after we've topped the range coming back, so this engine just pushes the logs in front of it until we're on the slope and gives us a shove off. My cobber and I - there's only two of us travel on the logs - hang on to the moving trolleys and brake them as they gather speed. We get up to thirty miles an hour coming down. Coast right into the mill almost.

"Dangerous?" He laughs. "Safe as houses. They might get away from us of course. But then we'd just jump off. We DID lose four heavy logs a week or so ago. They came round one turn hell-for-leather, beat the brakes, and we had to let 'em go. Sixty miles an hour or more they must have been travelling when they jumped the rails and crashed into the valley. Some row they made too. Bad as France again."

Hikers at the entrance to The Bump Tunnel

Through the tunnel

"And here we are at the tunnel."

Cold air swirls out of a black, square opening in the mountainside, right ahead. Plunging into the gloom and coolness, the engine squeezes past the entrance to the tunnel, seeming to scrape the roof and sides. There is noise and tumult. Echoes are flung from rails to roof.

Light dims and grows dimmer. Behind, the square which engulfed the train has changed to an eye of blinding sunshine glaring into the blackness. Further and further into the bowels of the mountain . . .

"Thousand feet long!" screams a voice in your ear. Faintly the invisible engine begins to take shape once more. Light struggles round it and filters through the smoke beating against the low roof of the tunnel. Then abruptly the engine has burst into the open and the heat again.

There is a dip and a slope outside the tunnel. With increased speed, the train rumbles around a curve and ventures over a gurgling creek which splashes between green ferns.

"Looks cooler here," says the timber man, "but we want a fall of rain to make things quite safe from bush fires. Anyhow, I'd rather have summer conditions than winter. Coming home hot and drenched with perspiration is a damn sight better than coming home cold to the bone and drenched with rain."

He shakes his head decisively and, with a sudden "We're here!" leaps to the ground to overhaul and pass the engine in half-a-dozen long easy strides.

In a cool, wooded glade, the train halts, hesitatingly, doubtfully. You jump down and stretch your legs in the shade of the silent, towering gums. The sound of an axe meeting hardwood somewhere to the left is the only sound that issues from the dense jungle.

There is a siding on the right of the log train, a siding loaded with ten huge logs on low trolleys and strung together heavily behind another locomotive.

The return journey

Seven or eight timber-fellers materialize from the trees. Axes are dropped as the engine-driver cheerfully flourishes a packet of letters and bundle of newspapers.

"Got a good load for you today, Jim," says a bare-shouldered axeman, whose rippling muscles threaten to split the dark skin of his upper arms. "Ten snifters! Eh? No, no fires yet. Still they'll come if it doesn't rain. And of course it won't. One shower'd be enough, too. Just one."

He squints up at the hot sky and glaring sun, shrugs his shoulders resignedly and fills his pipe.

With a minimum of effort the empty trolleys are kicked behind the local engine, ready for tomorrow's trees. The Powelltown locomotive shoulders its way behind the ten patient logs. Two men pass slowly along the line of trolleys and their tremendous burdens, adjusting the wooden brake blocks, tugging, pushing and testing.

"Better sit on the end of this last log," your recent friend advises. "Make yourself comfortable, but hang on when we start in earnest. And mind the roll; there's three or four inches of play allowed for each log."

You seat yourself on the smooth rounded trunk, dangling your legs over one side. There is nothing which you can grasp for security except one of the links in the stout chain which shackles the log to the low trolley. And you can only jamb one finger through that. However . . .

The two brakemen have clambered on to the leading logs. One of them waves his hand. The engine whistles and pushes forward. The heavy logs are thrust into motion.

Things are quite comfortable at first.

True, the log shakes and strains and trembles and slips and groans and gives every promise of breaking at any moment from its chains. And certainly it has a disconcerting habit of slithering backward and forward as it negotiates curves at the rear of its nine brothers. But, with the reliable old engine puffing confidently behind you, and the speed of the swaying logs a mere fifteen miles an hour or so, there is no cause for alarm or even apprehension.

Why, there is one of the brakemen walking along the logs as they lumber through the thick scrub and thread their way ponderously between the trees, passing from one moving log to the next as casually as though he were walking down Collins Street.

Through the tunnel once more, however, and the engine uncouples and falls back to follow at its restricted speed limit.

"Hang on!" bawls the nearest brakeman.

You refrain from the obvious reply and sit more rigidly. Dipping, the logs pitch clumsily down the grade. Staggering, they rock with gathering speed around a curve. They plunge awkwardly down hill swayed by their weight and rolling under the chains. Perched on the end, with your legs braced firmly against the side of the huge, trembling log, one hand flattened firmly along the surface, and one finger of the other twisted through the imprisoning chain, you endure the jarring and shaking with an assumption of calmness.

Another curve jerks the length of each log in turn and sways your seat back three or four inches. It seems like three or four feet. The chain is forced back and jambs your finger. Painfully you re-adjust the crushed digit and slip it into the next link. Playfully the log straightens and, slithering back, nips your finger a second time.

One of those trestle bridges-much narrower than when you climbed it an hour ago-trembles under the clamorous passage of the great logs. Your legs are swinging a hundred feet or more above some very solid-looking ground and rocks. Extremely solid looking. You lean back a trifle. And you recollect that if you had eyes in the back of your head they would witness the same inspiring spectacle, the same lofty drop and the same solid looking rocks behind you. So you sit bolt upright.

Those trees are flashing past pretty quickly. Thirty miles an hour or thirty-five? That fellow said they had once gone as fast as sixty miles. That time, though, they had to jump off because the logs had got away from the brakes.

Mechanically you measure the distance between your helpless feet and the rough track whisking away beneath. Of course, it COULD be done. But suppose they shouted to you to jump off when they were in the middle of another trestle bridge?

Your disturbed reflections are rudely interrupted by a gust of wind which plucks suddenly at your hat. You effect a smart rescue, and blink off the blue clouds of thick smoke which rise from the tortured wooden brake blocks to envelop the log from end to end. Dimly, as in a fog, you glimpse one of the brakemen hauling desperately at a brake lever in front of him. You can't see the other man. No doubt he has fallen off . . .

The influence of those sturdy brakes is being felt now, however. Speed slackens. The acrid smoke abates. Gingerly you shift your position. There is nothing soft about a fresh felled log.

Another trestle bridge rumbles sonorously. You avert your gaze and glance along the logs. No sense in looking down at the drop below. You are relieved to observe that the front brakeman has not fallen off. He's -yes, he has just taken his hat off to scratch the back of his head.

Swinging to the right, the logs sweep through a cutting, curve round a sandy embankment, brush past overhanging bushes and stagger to a standstill within sight of the nearest houses of Powelltown. The brakemen walk leisurely back to where you are sitting, assessing bruises and nursing a black finger nail.

"Good run, eh?" says one. "We've got to wait now for the engine to catch up. There's a bit of a rise here. Only a quarter of a mile or so to go and we'll be back at the mill.

"Why, listen."

Like the distant buzz of angry wasps, the eternal drone of the Powelltown sawmill floats towards us. And a red sun is sinking behind the tips of the tallest gum trees.

By Hugh Richards. From the Victorian Railways Magazine, February 1928.

Views since 26 August 2015 .